People Bathing

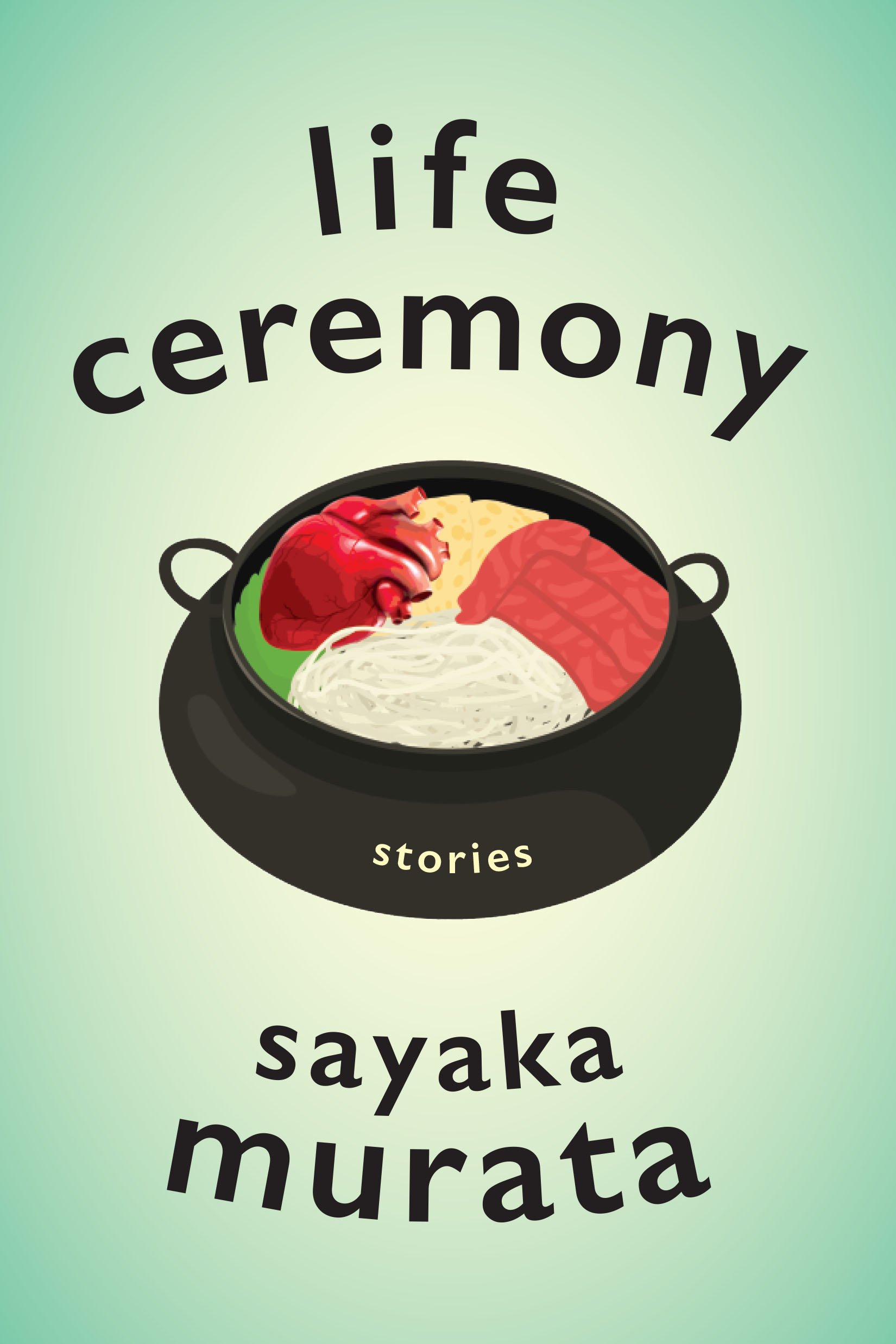

Life Ceremony: Stories By Sayaka Murata

By Sayaka Murata

GROVE ATLANTIC, JULY 2022, 256 PP.

REVIEWED BY KATHLEEN ROONEY

Horror is a genre full of feminist potential. In a talk at the 2020 Horror of the Humanities, an annual Halloween event hosted by DePaul University, philosophy professor and Humanities Center Director H. Peter Steeves made the point that horror is an excellent vehicle for feminist messages and interpretations, its plots often hinging on a disbelieved woman. The female protagonist is the only one who perceives how screwed up a given set of circumstances really is. In this sense, horror is analogous to the day-to-day experience of living life as a woman, feeling confounded by an eeriness which other people refuse to acknowledge.

In her brief and offbeat 2016 novel Convenience Store Woman, which has sold over a million copies globally, Japanese author Sayaka Murata offered an unsettling but essentially realistic depiction of a thirty-six-year-old woman who, after eighteen years in the title job, can barely comprehend her own identity outside her employment. In Life Ceremony, Murata’s first collection of short stories to appear in English, her narratives are conspicuously weirder, weird in the sense of weird tales—dark and macabre, surprising and strange. The twelve stories blend humor and horror to examine societal norms, and to expose how bizarre and oppressive certain social standards and traditions can be, especially for women.

“A First-Rate Material,” the opening story, depicts a world in which “making people into clothes or furniture after they die” is a common practice: sweaters woven of human hair, engagement rings fashioned from fibulae, chandeliers hung with hundreds of fingernails. The protagonist, Nana, believes that such items are noble, better than allowing corpses to go to waste, whereas her fiancé, Naoki, asserts that they’re barbaric. The conflict hinges on this putative Prince Charming’s almost fairy-tale threat when she goes to purchase furniture for their new home together: “If you choose even just one item made from human products, I won’t marry you.” Although Nana finds his aversion to be ethically inconsistent—why, she wonders, seeing him in a cashmere sweater, is goat fur fine?—she swallows her opinions in favor of keeping him happy, until a twist throws his values into question after all.

Murata returns again and again to themes of production and consumption, both in the commercial and in the bodily sense—the things people purchase and the things they eat, as well as their stated and unstated motives for doing so. In “A Magnificent Spread,” the story of a woman helping her little sister, Kumi, cook a meal for her fiancé’s family, the characters discuss the practice of “eating weird things” in a manner that underscores how it’s kind of weird to have to eat at all, and how it’s equally odd to assume without any discussion that a wife “would carry on the food traditions” of her husband’s family.

Like so many others in the collection, this story illustrates how behaviors and customs that their practitioners accept as solid and given are actually arbitrary and relational and could just as easily be seen as silly or abhorrent in a different context. Dining in an upscale Italian restaurant, the narrator explains to her mother and Kumi that “this pasta with peach and coriander—since it’s made in a restaurant like this by a respectable chef, I can delight in eating it”; however, if “one of the local elementary school kids brought it in a Tupperware box [. . .] I’d probably think pasta with peach sounded disgusting and wouldn’t be able to eat it.”

Human beings frequently like to think of themselves as consistent; they like to view their principles as reasonable and absolute. Yet by taking any premise to its most extreme and absurd conclusion, Murata explores how slippery and self-justifying a lot of activities are. Over and over, her characters discover that structures and hierarchies exist not because they are elegant or natural (or even because they are just and sustainable) but merely because certain segments of society have found them to be expedient.

In the long, not-quite-novella-length title story, “Life Ceremony,” cannibalism lets Murata push her critique to its most acute expression, one that’s as grimly funny as it is disconcerting. “When I was little,” Iketani, the first-person narrator, a nondescript office worker, recalls, “it was forbidden to eat human flesh. I’m certain it was,” but now “the custom of eating flesh has become so deeply ingrained in our society that little by little, I’m becoming less confident about what things were like before.” In this new paradigm, when a person—such as Mr. Naoko, a higher-up at the company where Iketani works—dies, their loved ones hold a life ceremony at which the guests consume the body of the deceased. Attendees also engage in “insemination” because the population has plummeted to such an extent that the human race is faced with potential extinction. “This has had the effect of procreation morphing into a form of social justice,” Iketani remarks.

Murata’s signature matter-of-fact tone makes this off-kilter reality both viscerally and intellectually provocative. The narrator explains that she is less upset by the cannibalism itself than she is at how, thirty years ago, when she was a schoolgirl, she was ostracized and reprimanded for making an offhand joke about eating people. Her reluctance to participate in the practice as an adult is not because she believes that it should still be taboo, but rather because “I felt indignant that the ethic by which I’d been judged had turned out not to exist in the first place.”

Translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori, Murata’s style is deceptively blunt and direct, making for a lightning-quick read. And yet, the stories’ haunting premises linger in the mind. Even the very short stories, which initially struck me as high-concept but slight, got stuck in my head. “Poochie,” for example, tells of Mizuho, who has a crush on her friend Yuki, who in turn has a secret pet. Mizuho is confused and repulsed to find that this creature is a middle-aged man “about the same age as my dad.” Poochie, she observes, “gave off the stench of a wild animal, and the pale skin on the top of his head felt sticky,” but she makes herself accept him because of her affection for Yuki. At first, this story appeared to me to be a clear-cut commentary on the grind of adult office life to which almost any other existence is preferable. “He hardly ever made a sound. Just occasionally he would cry, ‘Finishitbytwo!’” Mizuho notes, concluding that, “This was probably an order he used to issue” back in the Otemachi business district near Tokyo where Yuki found him. But the more I think about it, the more I realize that I can’t boil the tale down to any one interpretation, which is more fulfilling than if it had a single allegorical point. Life is ineffable, these stories remind us, its circumstances more mutable and multifarious than we may initially believe.

Similarly, the story “Lover on the Breeze” expanded in meaning long after I’d finished reading. The narrator, Puff, is a blue curtain hanging in the room of a young girl, watching as she comes of age. The story seems at first to put a spin on the theme of unrequited love but gradually becomes as creepy as it is sad and sweet, exploring voyeurism and consent as much as growing up.

The sense of relativity that recurs throughout these stories feels scary but also perversely liberatory—as though in Murata’s worlds, anything could happen, marvelous or terrible. In “Puzzle,” the protagonist, Sanae, revels in the crowded Tokyo subway:

Submerged in air full of sighs released from numerous mouths, she closed her eyes and savored the dampness on her skin, floating in it, happy being smothered in the carbon dioxide spewed out by passengers. Long ago the term forest bathing had been popular, but Sanae preferred ‘people bathing’ like this.

Maybe that’s the best way to immerse yourself in Murata’s peculiar realms—to understand that the experience will be bewildering and probably a little bit gross, but satisfying if you give in and let the weirdness wash fully over you.

Kathleen Rooney is the author, most recently, of the novel Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey. Her poetry collection Where Are the Snows, winner of the X.J. Kennedy Prize, is forthcoming from Texas Review Press in fall 2022, and her novel From Dust to Stardust will be published by Lake Union next year.