The Beautiful: small scale, gentle luminosity.

Sublime: territorial, vast, craggy, un-

domesticated, borderless, immense, unknown,

awful, monumental, transcendent, transcending.

—Elizabeth Alexander, “American Sublime”

Amy Sherald’s current exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art, American Sublime, fills in through image and word a crucial absence in American painting. Sherald’s portraits stake their territory neither in the wilderness or land to be conquered, nor in the transcendent as conceived by American Protestant traditions. Instead the subjects of these paintings pursue the pleasures and illusions of ordinary daily life. Her extraordinary use of titles glosses her reading of essential American literature—Lucille Clifton, Toni Morrison, Elizabeth Alexander—but she employs her own wit and talent for compression with an uncanny accuracy to place her subjects. (How many of us could be titled Well Prepared and Maladjusted?) Her own ambitions to signify, though, never slight her subjects’ ambitions: to perch on a girder in the sky, to ride a hobby horse or a dirt bike like a racehorse or a bull, to frolic at the beach, to command a tractor, to kiss, to wear a dress.

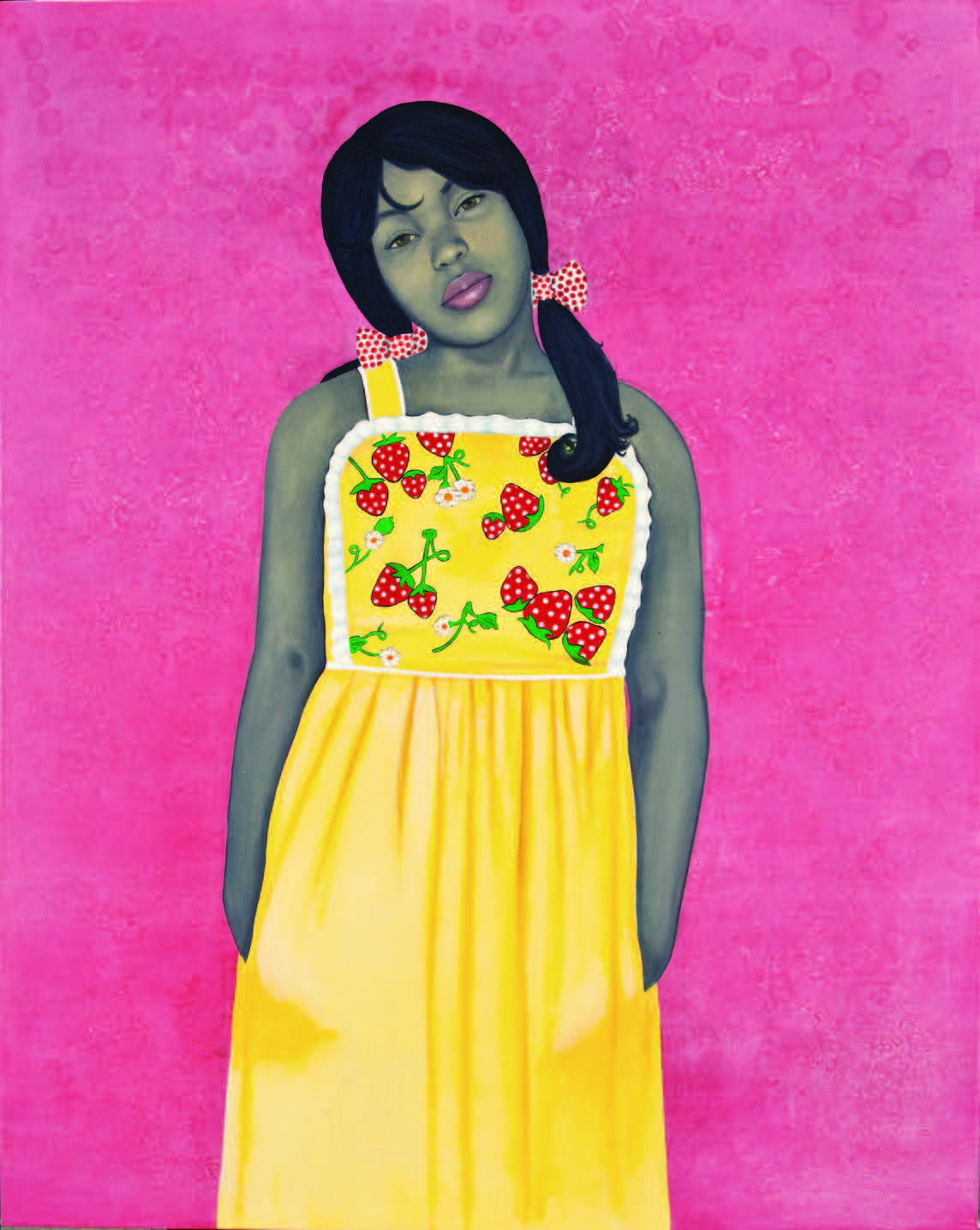

Our cover this month, They call me Redbone, but I’d rather be Strawberry Shortcake (2009), is an early career painting of Sherald’s. Her subject is a girl on the cusp of adolescence wearing a yellow pinafore-style sundress, its bodice studded with plump strawberries looking very little like the actual fruits. Also rendered abstractly are the hair ribbons patterned with strawberries that hold her long straight hair. Her lips are full and pink, a more lifelike strawberry; her limbs are rounded and formless as a child’s. It is her expression that stops a viewer short. Sherald manages to convey a sense of innocence clung to but already violated. Her title ensures that what is on the canvas won’t be misread. Rendered in shades of gray, as in Sherald’s other portraits, the color of a child’s skin should be the last thing from her mind; society has made it the first.

As many girls do at her age, this subject clings not to a doll but to the idea of herself as a doll. Strawberry Shortcake was a ubiquitous image of plump cuteness that from the late seventies made its way from greeting cards to actual dolls and eventually to cartoon characters, all easily dismissed as kitsch. It is Sherald’s nonpolemical genius to suggest not so much a black child’s attraction to a white doll as the child’s desire to remain innocent and to be seen so. We can see this same hard-won, staunch sense of self just as purely in Sherald’s best-known works: a Breonna Taylor portrait that appeared on a Vanity Fair cover and Michelle Obama’s official White House portrait. Here again is a pleasure in dress, a wariness of being observed, an awareness of one’s vulnerability to imminent threat. If Sherald’s portraits can seem flat in reproduction, they are shockingly intimate in actuality.

She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them (2018)is the title of another portrait of a seemingly ordinary woman, who here bears a multistranded choker of large stones or beads as regally as a queen. It suggests, again, where the artist has located the sublime: inside the self, best defended by a carefully composed outside of “small scale, gentle luminosity.”