Along with the National Organization for Women and the American Association of University Women (AAUW), Ms. magazine was feminism when I was a kid. I grew up in 1970s Fargo, where my mom subscribed to Ms. and was a member of AAUW. A Ms. mom was different than a mom who read Ladies’ Home Journal, less likely to sew clothes for your Barbie doll or make bread-dough ornaments (though my mom baked her own bread). This was before I knew much about the factions, cliques, or origins of the second wave, so I didn’t think of Ms. as radical for a magazine but mainstream compared to groups like Redstockings, Cell 16, or others formed by earlier feminists in major American cities. Redstockings preferred the term “women’s liberation movement” (WLM); all three words were crucial to their project. Still Ms. was how women in North Dakota and probably most places accessed the movement’s ideas.

Ms. was key to my 1980s too. During the backlash against “women’s lib” and the rise of postfeminists and “I’m not a feminist but I’ll take that abortion, thank you” feminists, Ms. was rebooted ad free, and in college I read it Talmudically with my sisters in Downer Feminist Council (not the best name). By the 1990s, I worked at Ms., and then I spent 1999 to 2015 or so traveling the country with Amy Richards, translating feminism to the feminist fearful and feminist curious.

There is, I’ll admit now, a negative side to popularizing feminism. At times, the term “feminist” is cut off from feminism’s particular history, cast of characters, and intellectual roots. This is obvious, but Instagramming oneself in a “This Is What A Feminist Looks Like” T-shirt doesn’t entail the same commitment nor payoff as four years of in-person consciousness-raising meetings. It’s a gesture but not likely to help with unplugging from the Patrix, becoming liberated, or helping to build a movement. Identifying as feminist has never been so acceptable as it is today, yet the grasp of feminist history can run from overbroad (the second wave was racist and transphobic) to downright bullshit. Take, for instance, the notion that in the 1970s, feminists “identified their gender as lesbian”—which has popped up in my class at Smith and also at a Q and A I was part of after a performance of Liberation (more on that in a second). Each time it was stated as fact, and yet I haven’t found any evidence of it in my research or reading, or in forty years of getting to know activists in that movement. Is it a TL;DR misreading of the “The Woman Identified Woman” manifesto by the Radicalesbians (May 1, 1970) mixed with the 4B movement (2024), reshared until meme becomes memory?

While Gen X through Gen Z can’t help that we didn’t attend the Second Congress to Unite Women in 1970 (where the WIW manifesto debuted), there are trusted sources for understanding feminism then, when the insights came fast and revelations were fresh. The most convenient way is via the many books, manifestos, and other first-hand accounts written by the feminist instigators. Here’s Vivian Gornick in The Feminist Memoir Project: Voices from Women’s Liberation (1998) recalling her confusion, in November 1970, when her editor at the Village Voice suggested she cover women’s libbers. “What’s that?” she asked. She learned:

In the first three days I met Ti-Grace Atkinson, Kate Millett, Shulamith Firestone; in the next three, Phyllis Chesler, Ellen Willis, Alix Kates Shulman. They were all talking at once, and I heard every word each of them spoke. Or, rather, it was that I heard them all saying the same thing because I came away from that week branded by a single thought . . . the idea that men by nature take their brains seriously, and women by nature do not, is a belief not a reality; it serves the culture and from it our entire lives follow. [Italics mine, to underscore her rad insight.]

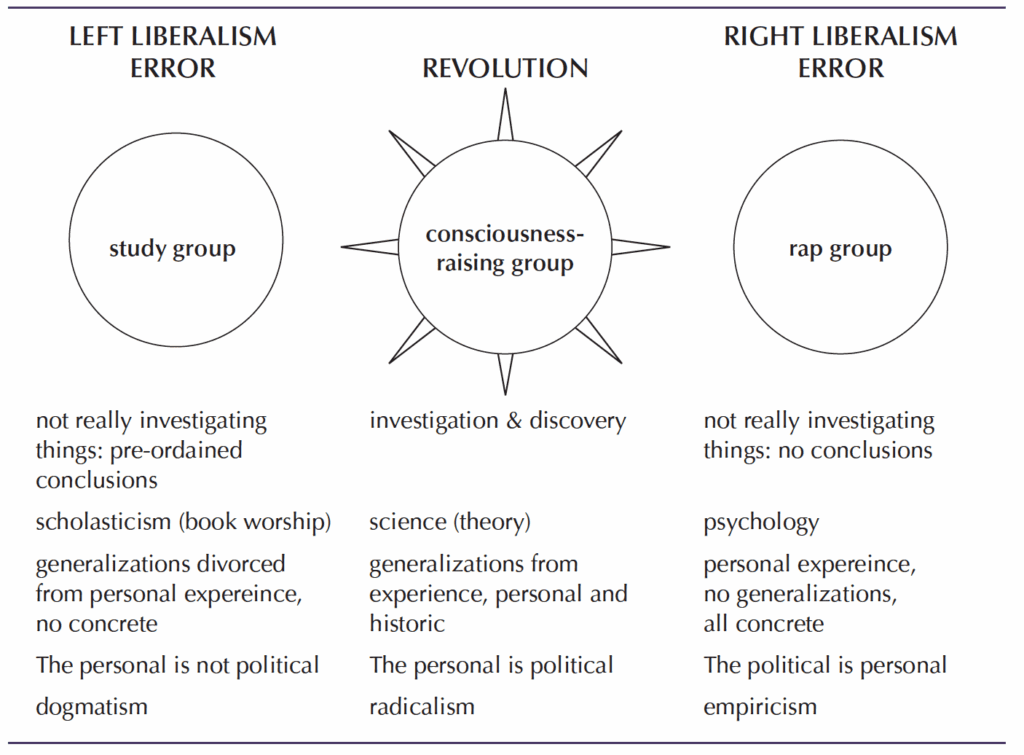

Then she writes, “I stood in the middle of my own experience, turning and turning. In every direction I saw a roomful of women, also turning and turning.” I mean . . . that is what feminism looked like! Like a rave and a seminar to root out one’s own misogyny and learned passivity! The mechanism—really a practice—for this movement was consciousness-raising (CR) and/or “rap groups.” (Although Redstockings begged to differ. See figure 1.) During this time of rapid, exhilarating change, women gathered in person, with regularity, to try to tell the truth about their lives, and in that commitment to taking themselves seriously, in that curiosity about women and their own experiences, got free from the overstory they’d been sold about who they were.

Dramatic though it clearly was, the 1970s feminist revolution has proved hard to dramatize. Take, for instance, The Janes (2022), Call Jane (2022), and Ask for Jane (2018), just three recent films about the illegal abortion service. All three are flat-footed and surfacy, devoid of the verve and revelation found in the low-budget documentary Jane: An Abortion Service by Nell Lundy and Kate Kirtz (1995). Similarly I revel in the chic derring-do of Germaine Greer topping Norman Mailer in Town Bloody Hall (D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, shot in 1971 and released in 1979), but that spark is not captured in, for instance, FX’s Mrs. America (2020), with its silly period wigs and de rigeur famous waif playing Gloria Steinem with her aviators. Question: Does feminism resist production values?

Liberation, a new play by Bess Wohl (whose Grand Horizons received a Tony Award nomination for best play in 2020), has the distracting wigs, but her dramatization of a daughter trying to understand her mother in the context of a CR group in 1970, before she was born, is powerful connective tissue. Directed by Whitney White, the entirety of the play is set in a high school gym somewhere in Ohio. The six women who form the group are a little schematic: the homeless-ish lesbian who pens a “Womanifesto” (the words are verbatim from the Redstockings Manifesto); the unappreciated empty nester who makes cheese balls and wants to stab her recently retired husband; the pretty one who has never had an orgasm; the Italian who yells and talks with her hands; the strong black woman academic back in Ohio to care for her dying mother. Susannah Flood (she was Amy Schumer’s sister on Hulu’s Life & Beth) is on stage for the entire two-and-a-half-hour show as Lizzie, a cub reporter stuck on the weddings beat who initiates the group, and also as Lizzie’s daughter, a present-day millennial mother who is alarmed by all we’ve lost. As the daughter, she often speaks directly to the audience, translating bits of trivia so the period characters (who don’t break the fourth wall) aren’t burdened with exposition. Over the next few years, using prompts from that newfangled magazine Ms., the women help each other to become stronger and more realized.

Bess Wohl’s actual mother, Lisa Cronin Wohl, wrote for Ms. in the seventies. In fact, Letty Cottin Pogrebin (a cofounder of Ms.) directed the playwright to her Ms. article “Rap Groups,” about her own group, which met on Tuesday nights from 1972 to 1976. “These were the first years of Ms. and part of the first six years of my feminism,” Letty told me. “Before that: I was oblivious.” Betty Dodson, famed for her orgasm workshops, was in this group, as was Anselma Dell’Olio, the founder of the New Feminist Theatre and an early survivor and theorizer of WLM “trashing” (basically, canceling). Their group “would talk about everything, for instance the way that women shrunk themselves to be with men,” Letty recalls. “Every session was so fucking deep that you left it transformed.”

The first act of Liberation is entertaining but a bit cliché ridden. Letty told me she thinks the broad strokes are intentional—to convey the daughter’s spotty understanding of a CR experience and her mother’s younger life. The second act, which opens with the group disrobing completely for the meeting and identifying one thing they hate about their body and one thing they love, is where Liberation begins to fly. It’s memorable: emotionally naked and very compelling, yet not titillating or gimmicky.

I wondered if it was meant to take the place of self-help gynecology (à la Carol Downer, RIP) or even Betty Dodson’s masturbation workshops, since those both figure prominently in WLM histories and nudist CR hadn’t ever pinged my radar. Then I read Letty Cottin Pogrebin’s “Rap Groups,” both its hand-edited draft in the Smith archives and the final published in Ms. Just as Letty had told me, many of Liberation’s CR scenes—including meeting in the nude—were right there in her piece.

The draft lede from Letty’s article “Rap Groups,” which ran in the March 1973 issue of Ms. (mis-dated “1972” in this draft). Image courtesy of the Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History at Smith College

In the play, when the group eventually disbands, each newly self-realized woman must confront conflicts and contradictions in her own life. Lizzie gets engaged to a hunk with a real seventies mustache (he’s the only character we are set up to ogle), and her confession that she will follow him to New York is so shame filled, it’s as if she was admitting she was off to join Phyllis Schlafly. WLM veteran Barbara Winslow’s CR group met twice a month. She loved the play, and during the CR “confession” scene, a vivid memory came back, which she had earlier recounted in The Feminist Memoir Project:

One very painful session for me dealt with “who drives the car.” I admitted to everyone’s shock that I could never challenge my husband on the issue of driving the car. Even though I was a good driver, his constant criticisms and belittling of my skill was not worth the fight—or so I thought then. My sisters in the group really went after me for that. I decided not to admit in our CR session on housework that even though I was a committed women’s liberation activist it didn’t seem worth the fight over housework. I cleaned the house, shopped, and cooked. He mowed the lawn. I always felt like a fraud in our CR group.

There were contradictions and evasions in this era of feminism, but also genuine revelation, growth, and freedom. At root, committing to these meetings required taking oneself seriously, and Liberation portrays the CR group as a kind of university for self-love and self-curiosity, which, once found, extended to being curious or amazed by women. Elizabeth LeCompte (creative leader of the Wooster Group) refers to this magical liveness in theater as a “reaction,” as in an event in which two or more substances act mutually upon each other and are transformed. This interpersonal, IRL manifesting is where CR and live theater intersect, and quite possibly why Liberation was so palpably an expression of feminist memory.

By the way, there was a kids’ version of Ms. in the 1970s, and I don’t mean Stone Soup. I’m talking Free to Be . . . You and Me, the beloved record, TV special, and (eventually) book. A recent show at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst featured visual artifacts (vintage photos, records, letters), illustrations, and animation cels from that glorious Gen X touchstone.

Like the hundreds of thousands of families who bought it, I love the record (1972), but the TV special (1974) is how you get the full experience: Dig, if you will, a Borsch-belt newborn puppet voiced by Mel Brooks boy-splaining to Marlo Thomas’s girl infant that, actually, he is the girl. I wanted to be a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader at around the same time I first encountered Free to Be based on their outfits, so when Mel yells that he wants to be a “cocktail waitress! Does that answer your question?” I really felt like it did. Feminine and masculine roles were just that. Roles—and arbitrary. Free to Be was not just touchstone but shorthand for the second wave promise of freedom from stereotypes, a mass-market delivery system for feminism, connective tissue between seventies feminist mothers and their children.

I listened to the songs from Free to Be . . . You and Me from my current vantage point (midfifties writer living in New York City with two teenage sons). I was struck by how clearly the songs, stories, and sketches translated second wave feminism into common sense without being boring and treacly. Even more impressive are the participants in this project. This is “We Are the World”–level wattage a decade before that landmark. Judy Blume, for one, whose books I devoured (she delivered more sex ed than all health teachers combined), contributes the story “The Pain and the Great One.” Alan Alda is both the phobic father in “William Wants a Doll” and the princess’s enlightened suitor in “Atalanta.” The poet Lucille Clifton contributed the story All Us Come Cross the Water, the football player/knitter Rosey Grier sings “It’s Alright to Cry,” and urbane talk-show host Dick Cavett performs the poem “My Dog Is a Plumber.” Michael Jackson and Diana Ross sing about puberty in anxious, honest questions in “When We Grow Up.” Parents are revealed to actually be just “people” but with children. They are busy and purposeful. Harry Belafonte drives a cab, Marlo Thomas jackhammers the streets of New York, and they both push baby strollers. Also word to the wise: housework sucks, so don’t dump it all on your mother! Instead, as Broadway legend Carol Channing rasp-exhorts, “do it . . . together!”

When I visited the Free to Be . . . You and Me exhibit at the Eric Carle Museum, Jennifer Schantz, the museum’s new executive director, explained that the Eric Carle is not a children’s museum but a gallery that “elevates the art and artists of children’s literature.” Unfortunately this narrow remit doesn’t play to the strengths of Free to Be, the multimedia phantasmagoria. The creative power is not captured with this spate of animation cels and drawings that curator Margi Hofer tracked down. You need the music and the theater and the sketches to dramatize its humorous upending of gender roles. I understood that message at age four and still do at age fifty-four: the individual is free to be whoever they are.

The opening song of the Free to Be TV show and record makes me cry to this day. “Every boy in this land, grows to be his own man. In this land, every girl grows to be her own woman.” It’s a wish for children to create the world that they want and a pinky promise to support them becoming themselves. Given the skimpy version of Free to Be the Eric Carle show managed to evoke, I was annoyed to see a placard dedicated to explaining that although “Boy Meets Girl”—the classic Mel and Marlo baby sketch—was “progressive in its questioning of traditional gender roles” its “portrayal of gender identity as male-female binary linked to biological sex seems outdated today.”

I was further annoyed to see new theme song lyrics by Sara Bareilles (written in 2020 at Marlo’s invitation) that just clunked. “Every child in the land, may you all understand, that you’re proud and you’re strong and you’re right where you belong.” The sentiment is bland, trite, and not even true. You can’t conjure belonging and security rhetorically. You can model it and imagine it as a place we are heading to, the “land that I see” of the original song. To denature this work is so odd and misguided. It implies that Free to Be was not radical, when we haven’t yet achieved the world imagined within the original.

That said, I will dunk a bit on another classic taken out of its usual context: Macbeth. It’s a play that I love, but a recent take made me see new valences that are relevant here. A week after Liberation closed, its director, Whitney White, starred in a metacritique of Macbeth at Brooklyn Academy of Music (she also wrote and directed). White’s Lady Macbeth is a gorgeous, glam diva backed up by three Dreamgirls-esque witches. White also plays herself, a black actress confronting what is available to her from Shakespeare, who wrote a wide array of men and some ingenues. Lady Macbeth, the meatiest female character, is a lead she covets.

The witches ask White (and Lady Macbeth) what she wants, but it’s hard for her to spit it out. Finally she says, “Power.”

“What do you mean?” they press.

As she tries to articulate the specifics, Macbeth keeps interrupting, shirtless (Charlie Thurston, the same hunk from Liberation) and honking away on his accordion. They cycle through the major plot points, but White is increasingly aware that even Lady Macbeth gets the Eve treatment—as in all the blame and none of the power. In fact, hers is kind of a small role. And when she dies, it’s offstage.

Forsooth, we are still working on being the lead, even in our own minds, but keep at it. What do you want? Be more specific. Or as Vivian Gornick puts it in that Feminist Memoir Project essay, “If I held on to what feminism had made me see, I’d soon have myself. Once I had myself, I’d have: everything.”