Spent,the new comic novel by Alison Bechdel,is a study in what happens when a doom spiral develops centrifugal force. The book is set in 2021, mid-Covid, both post- and pre-Trump. A fictionalized version of the author, Alison, and her wife, Holly, run a pygmy goat sanctuary on their Vermont farm. While Holly goes viral for her chainsaw sculptures, Alison attempts to write her latest book, $um: An Accounting, a memoir of the role of money in her life. It will “be a lens into the over-consumption, inequality, endless growth and media consolidation of late-stage capitalism! But first, she has to sell it.” When she gets an offer from the evil Megalopub, a corporation she protested when she was younger, Alison wonders, When did life get so complicated?

When I recognize some of the characters in Spent from Bechdel’s long-running comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For,I drive out to the library where, fifteen years ago, I first discovered that comic among the graphic novels, thrilling my sixteen-year-old heart, which already watched out for dykes with endless fear and hope. I live closer to that library now, go there every few days to write, and every time I walk in, I think, how much longer will a space like this exist? But I use it while it lasts and check out the damn comic book.

In a strip from 1988 called “Civic Duty,”Mo (the protagonist, who looks suspiciously Alison-like) refuses to get out of bed. “What for?” she asks her girlfriend. “I’m not getting up until the electoral college is abolished and George Bush is impeached . . . I’m not getting up until Israel and Palestine find a two-state solution and apartheid is completely overthrown . . . I can’t get up one more day and go out into a world where atrocities are being committed every minute with the taxes I’m working to pay! Why should I be a productive member of a society that thrives by oppressing everyone else in the world?”

Bechdel wrote this nearly forty (!) years ago, but find-and-replace the presidents’ names, and Mo’s past catastrophizing is identical to my own in the present. When did life get so complicated? It has always been this way, and also, it has never been this bad.

Spent is driven by the kinetic energy of contradiction, the alternative fact—even the genre, autofiction, lends itself to the theme. The parallels between fiction and reality are tongue-in-cheek: real-Bechdel’s classic graphic novel Fun Home becomes Death and Taxidermy, in which her closeted father is not a funeral home director but a taxidermist. Instead of the Tony-winning musical adaptation of Fun Home, comic-Alison’s book is adapted into an Amazon (sorry, “Schmamazon”) series that deviates further and further from its source material. On the Schmamazon show, we watch comic-Alison, drawn by real-Alison, watch TV-adapted-from-comic-Alison break her vegetarianism, first with a hamburger, then by cannibalizing her mother. (By the season finale, her father will be dropped into a volcano by a dragon.) Beside herself, Alison decides to write a show of her own. It’ll be a reality show, like Queer Eye or a Marie Kondo series, “only instead of superficial tweaks, I’ll show people how to free themselves from the grip of consumer capitalism and live a more ethical life!” In other words, a reality show companion to a book about consumerism that she has sold but not written.

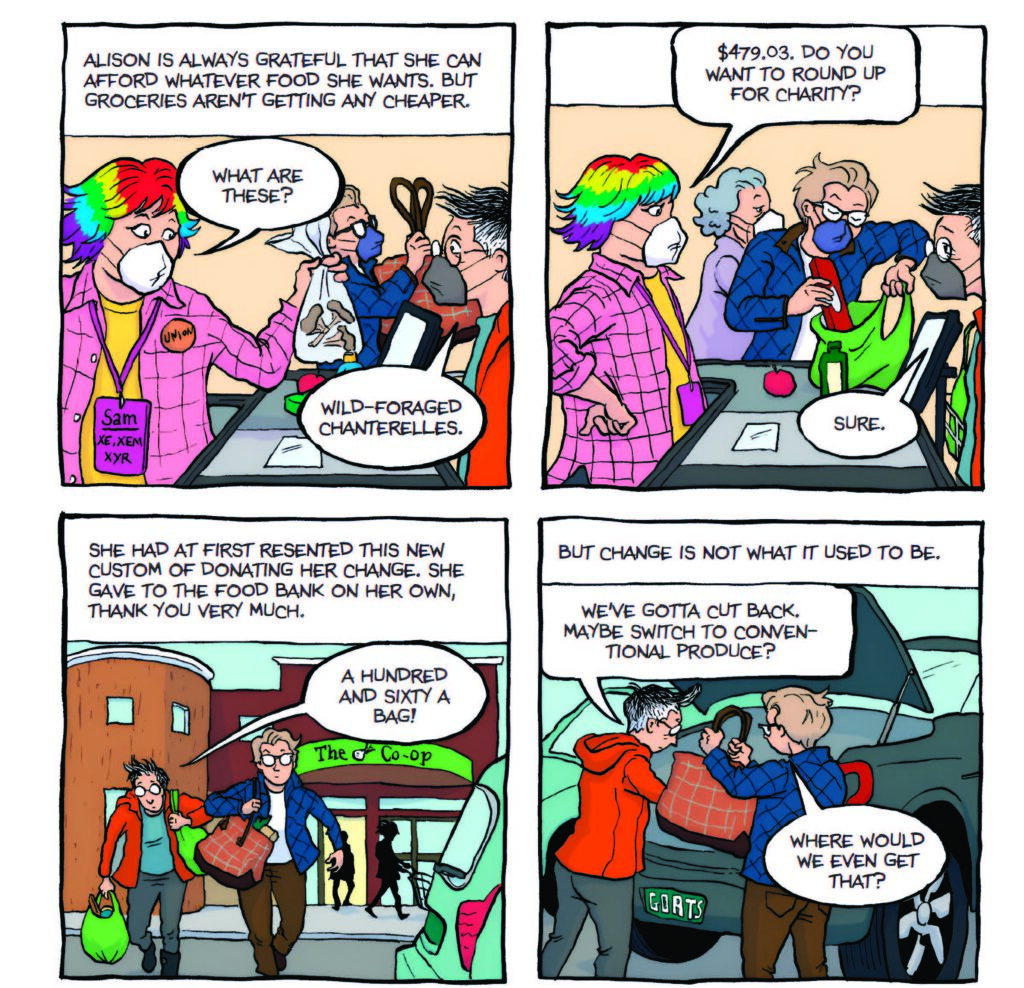

To free people from the clutches of late-stage capitalism, Alison must first figure out: What is late-stage capitalism? She tries to read Marx. She and Holly go over their yearly charitable contributions and realize they’ve only donated 4 percent of their income, well short of the planned 10 percent. But is donation helping anything or just propping up a flawed system? What they should really do is start a crypto-currency exchange. That,the thing that she will never do, would make a difference. These self-defeating attempts at living her principles leaves Alison in what is, for me, a deeply recognizable place: sitting in front of a blank Word document, engaged in the struggle that feels like work, but is only a complicated way to tire yourself out and do nothing. She raises her standing desk, pauses, lowers it again. She wonders whether doom-spiraling is a practical skill.

If this sounds gloomy or tiring, it isn’t. Spent conflicts with the assertion that we live in a postsatire world. Contradiction is the core of absurdity, the strength of one’s desire to find meaning in life matched equally by life’s resistance to meaning. Spent’s absurdity is justreally, really funny, both in its send-up of modern angst and its visual gags. The “plangent babble of confounded MSNBC anchors” weaves physically through the farm, tempering headlines on actual abortion bans with reports of pungent odors emanating from the Supreme Court. The chapters—called, appropriately, episodes—are named after sections of Marx’s Das Kapital and divided by splash pages of domestic life around the farm. Episode 11’s is my favorite: nothing epitomizes Bechdel’s mastery of the visual gag like “The Circumstances Which, Independently of the Proportional Division of Surplus-Value into Capital and Revenue, Determine the Extent of Accumulation,” etc., superimposed over a cat hunting a bird perched on a picturesque little birdbath. (The cat work in Spent is, incidentally, immaculate.)

One of the most compelling subplots involves erstwhile lesbian Sparrow and her husband Stuart, who have moved in with several other DTWOF characters as part of a “longitudinal study on communal living,” a sort of academic Hotel California where housemates can move in but never leave. When Alison invites “the beguiling Naomi” to the house’s Shabbat dinner, Sparrow and Stuart develop feelings for her independently, complete with a cartoon zing! and a lightning bolt when their hands touch, and they dive into the world of late-life polyamory. Their burgeoning throuple is stymied when their child, J.R., shows up unannounced in the middle of the trio’s attempt to satisfy one of Stuart’s convoluted fantasies.

The J.R. saga is the only one where Bechdel’s satire sometimes verges into old-man-yells-at-cloud territory. J.R. drops out of college after the implosion of their asexual polycule and makes the trip to the longitudinal-study-house in their girlfriend Badger’s electric BMW (bought by her crunchy-fascist parents). They opine on “Marxist relationship theory” and lecture Sparrow, a Planned Parenthood executive, when she doesn’t say pregnant people. At first, they seem to function as a vector for a series of easy dunks. This is remedied, though, by the narrative’s increasing awareness that J.R. and Badger are doing far better at putting their activist ideals into practice than the adults around them. They stage protests and start a podcast called Polycrisis, about “climate change and the economy through a poly, anti-capitalist, vegan lens.” Yikes, but soon, Polycrisis finds enough success to draw in famous guests and become their ex-Brooklynite neighbors’ favorite listen. A similar dynamic plays out with Sheila, Alison’s invented Trumpster sister. She’s silly in the opposite direction, with hobbies like crafting pro-life seed art and joining a Moms-for-Liberty-esque book-banning organization. And still, her character is balanced on that tricky slackline between predictable mockery and Republican apologism. She and the Zoomer duo remain ridiculous, but the story is kind to them in its loveably misanthropic way.

Spent’s overall atmosphere is summed up by such contradictions. It is a whole novel of hair-clutching doomerism that ends with an open-armed shrug and a smile. There is the crushing force of the daily disaster, but there is also the shelter of our own “annoying, tenderhearted, and utterly luminous friends.”