The Trouble with Angels (1966), a playful comedy about mischievous girls at a Catholic boarding school, was a beloved film in my family. My grandmother took her daughters to see it in the 1960s, and it became one of my mother’s favorites, rivaled only by Grease (1978). Growing up as she did in a large Catholic family with four girls and attending parochial school, my mother related to the film’s plucky lead (Hayley Mills) who matched wits with a stern Mother Superior (Rosalind Russell). I grew up hearing about it, absorbing her nostalgia until I finally gave her a DVD one Christmas so we could watch it together.

Yet one crucial detail had escaped my mother for decades: The Trouble with Angels was directed by a woman. When I mentioned Ida Lupino, the filmmaker behind her childhood favorite, she blinked in surprise. “I had no idea!” she said.

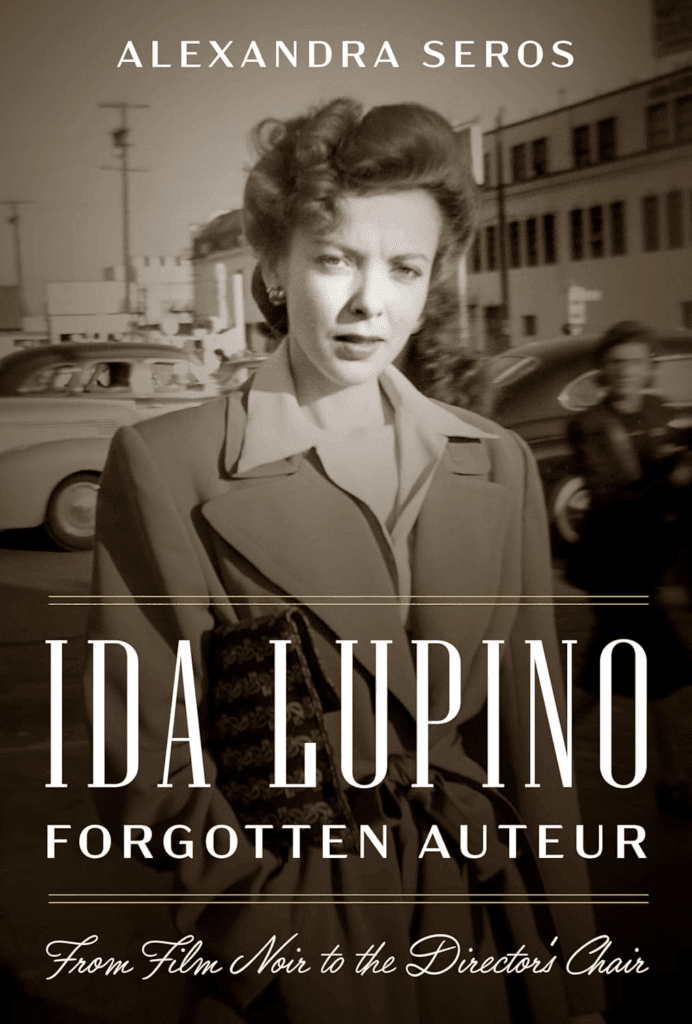

In fact, Ida Lupino was the only woman film director in postwar Hollywood. And yet, her directorial legacy remains largely overlooked. Studies of her career have been strangely scarce, and many are long out of print. As a corrective, Alexandra Seros presents Ida Lupino, Forgotten Auteur: From Film Noir to the Director’s Chair, an incisive study of Lupino’s work in film and television. Seros is a screenwriter with a PhD in Cinema and Media Studies from UCLA, where she is currently working to preserve film and early television movies directed by Lupino. Her book combines archival research with industry insight to illuminate an underappreciated visionary.

Born in 1918 into a British theatrical family with roots in early cinema, Lupino was immersed in show business from an early age. By her teens, she was already appearing in films and soon landed a Hollywood contract, frequently cast as a beautiful ingenue throughout the 1930s. As the 1940s dawned, she secured more substantial roles. Working with legendary directors like Michael Curtiz and Raoul Walsh (both of whom Lupino later cites as directorial influences), she refined a screen persona that mixed fortitude with elegance.

Though Lupino became an established star at Warner Bros., she grew frustrated with the roles assigned to her by the studio and her lack of creative autonomy. She was repeatedly suspended by the studio for refusing parts—a tactic commonly used by contracted stars like Humphrey Bogart and others to assert control over their careers. While suspended for eighteen months in the midforties, Lupino decided to try another route. In 1948 she founded her own production company in collaboration with her then-husband, producer and writer Collier Young. The company, called “The Filmakers Inc.” (deliberately stylized), was dedicated to creating low-budget genre films infused with social commentary. By keeping costs down, Lupino believed she could maintain the creative freedom she craved.

Over the next five years (1949–53), she produced, wrote, and acted in her own projects. Most significantly, she directed six films—an extraordinary feat, all the more significant because she was the only woman directing in Hollywood at the time. Her closest contemporary, Dorothy Arzner, had retired years earlier, and it would be decades before another wave of female directors—Joan Micklin Silver and Elaine May, for example—fought their way into the studio system in the 1970s. For roughly two decades, Lupino was the only woman in the Directors Guild of America..

Although she had no Hollywood counterparts, Lupino was not the only actress to transition into directing after WWII. In a section of the book titled “Lupino’s Global Cohort,” Seros examines other actresses-turned-filmmakers worldwide, including Japan’s Kinuyo Tanaka, a frequent collaborator of Kenji Mizoguchi. Tanaka may have drawn inspiration from Lupino’s career shift, making her directorial debut with Love Letter (1953) and going on to create a series of socially conscious films over the next decade.

Female directors remained a tiny minority worldwide, and the actress-to-director transition was one of the few available routes into filmmaking. “Lupino was subject to the same gendered expectations that other women encountered following World War II, but her extraordinary and sometimes unexpected skill level [caught] the attention of an industry dominated by men,” observes Seros. “Throughout her directorial career, she constantly navigated the gender politics of her era, balancing authority with social expectations.” To ease tensions surrounding a woman in charge, she often encouraged cast and crew to call her “Mom” or “Mother,” a strategic move that allowed her to lead without provoking resistance.

Seros compellingly situates Lupino alongside male contemporaries to make a case for her as a “forgotten auteur.” Like Samuel Fuller’s revelation of the horrors of the Korean War in The Steel Helmet (1951), Robert Aldrich’s evocation of nuclear annihilation in Kiss Me Deadly (1955), or Nicholas Ray’s depiction of teenage alienation in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Lupino’s films infused subversive and morally ambiguous themes into taut genre storytelling, probing the darker edges of postwar America. Together she and this cohort marked a gradual but significant shift in 1950s American filmmaking, smuggling provocative ideas into the B-movie framework.

Lupino’s style—a blend of Hollywood genre conventions and a more grounded, realistic approach—was also probably influenced by Italian neorealist films, particularly the work of Roberto Rossellini. These films often resembled documentaries more than polished studio productions, favoring on-location shooting and exploring complex social issues without the moralizing tone typical of Hollywood endings.

Unlike those of her male contemporaries, however, Lupino’s films tackled taboo subjects affecting women, subjects otherwise absent from postwar cinema: the plight of an unwed teen mother in Not Wanted (1949), the rape of a young woman in a small town in Outrage (1950), and the emotional consequences of a double life in The Bigamist (1953). Beneath the gritty genre surface, these are “empathetic stories” about “women in a dangerous, masculinist world,” Seros writes.

Of particular interest here is Seros’s discussion of how Lupino navigated the Production Code Administration (PCA), Hollywood’s self-imposed censorship body. For her directorial debut, Not Wanted (1949), Lupino initially faced pushback due to the film’s controversial subject matter; unwed, pregnant protagonists were absent from films of this era because the PCA generally suppressed any content that implied sex outside of marriage. However Lupino’s industry savvy and popularity among her colleagues allowed her to work around the censors. She personally visited the PCA offices and convinced them to lift their objections, knowing her star power and beauty was an asset to her mission. Seros writes,

Although her looks subjected her to gender discrimination, they also gave her agency, which she used to get what she needed. Lupino knew how to flatter and cooperate, and this allowed her to work around the obstacles she encountered. She walked the censors through the objected-to “adult only” scenes and secured their approval. . . . The censors insisted that the unwed mom not be glamorized. Lupino consented, and the project was green-lighted.

Lupino knew what kinds of films she wanted to make, and she used what was at her disposal to make them. But when auteur theory emerged in the 1950s in the pages of Cahiers du Cinéma, its mostly male critics largely ignored her directorial oeuvre. Andrew Sarris, who introduced the theory to American audiences, offered only backhanded, condescending praise: “Ida Lupino’s directed films express much of the feeling if little of the skill which she has projected so admirably as an actress.”

On the other hand, even as feminist critics brought attention to overlooked women directors, some were reluctant to accept Lupino as part of a feminist canon. Writing in the Village Voice in 1991, Patricia White praised Lupino’s acting while critiquing the female characters in her screenplays. Molly Haskell called Lupino’s films “conventional, even sexist.” Barbara Quart criticized “the anti-feminist content of her work” and “the gap between what Lupino herself did and the values she promulgated.”

Seros does not deeply explore the reasons for this second wave hostility toward Lupino’s directed work, though she describes how Lupino, at times, played on traditional gender roles in her public persona. She shared recipes and rejected feminist identity in the press. In 1965 Lupino told a reporter, “Keeping a feminine approach is vital. Men hate bossy females. . . . Often I pretend to know less than I do. That way you get more cooperation.” In other words, she was strategic. Martin Scorsese was a fan of her pioneering films that “far in advance of the feminist movement . . . challenged the passive, often decorative images of women then common in Hollywood.”

Nor did Lupino confine her work to women’s issues. Her masterpiece may well be The Hitch-Hiker (1953)—a stark film noir that, departing from the social realism of her earlier work, explores masculine power dynamics through a deadly game of cat and mouse on a desolate desert highway.

Although early feminist critiques “plagued Lupino’s legacy for decades,” Seros writes, later scholars like Annette Kuhn—who edited the anthology Queen of the ‘B’s: Ida Lupino Behind the Camera (1995)—have worked to overturn the earlier consensus. Seros sides with this more recent scholarship, arguing that Lupino’s films expressed a genuinely forward-thinking agenda. “She was neither fragile nor passive, and she was definitely not an anti-feminist,” Seros writes. “She explored the imbalance of power between men and women that was prevalent during the disruptive transitional period that followed World War II.”

After The Filmakers attempted to self-distribute their films when a deal with RKO (the studio founded by Orson Welles and now owned by Howard Hughes) fell through, the company collapsed in the mid-1950s, and Lupino had to refocus her career. She found a new avenue in television, which allowed her to stay in Hollywood while raising her young child.

In a welcome addition to the existing scholarship, Seros compellingly explores Lupino’s impact on television, which was both vast and significant, with over one hundred directorial credits spanning some of the most iconic shows in TV history. She collaborated with Lucille Ball, directed episodes of Gilligan’s Island and The Twilight Zone, and helmed gripping live dramatic productions. She frequently directed major Westerns and adventure series. Her ability to craft tension and high drama on tight budgets made her a sought-after director for shows like The Untouchables, Have Gun – Will Travel, and The Fugitive, proving her mastery of television’s fast-paced, high-stakes storytelling.

Much of her television work was in genres aimed at male audiences. Personally my first encounter with Lupino wasn’t through her films but via a guest appearance on the original Batman series starring Adam West, where she played the delightfully campy villain Dr. Cassandra.

This is just one more example of the astonishing range and complexity of Lupino’s career. And Seros makes a convincing case that she was far more than the sole woman who managed to direct films in postwar Hollywood. She was an auteur on par with any male contemporary, as well as a quiet revolutionary who consistently challenged conventions.