WHEN I LEFT Ms. magazine in 1997, one of the first people I called for advice was Ellen Willis. I was having an identity crisis. Ms., which had been my way into New York and journalism, was a dream job for five years, a place where editorial meetings entailed discussing the butch-femme dichotomy of Tonya Harding vs. Nancy Kerrigan, where even working the reception area meant fielding calls from Andrea Dworkin and Alice Walker. Without those credentials, who was I? I called Ellen Willis because, to me whose bible was Alice Echols’s Daring to Be Bad, she was feminist royalty. Ellen had worked at Ms. briefly, in the early days, and had quit in a sort of protest. I was hoping she’d affirm my choice, and we’d bond. Ellen took my call, but the only advice or gossip she offered about her time there was that she’d grown tired of being “the token radical.” Over the next decade, our paths occasionally crossed, and she’d offer insight, but infrequently, and she didn’t jump into the fray when debates grew heated on our history-in-action listserv. And then, in November of 2006, Ellen Willis died suddenly of lung cancer. Her daughter, Nona Willis Aronowitz, was a senior in college.

Nona’s next few years were a blur of grief, protecting her mother’s legacy, and starting adult life. She moved to Chicago, fell in love with a six-foot-five bartender/filmmaker named Aaron, and then married him, in part to share her health insurance. Aaron helped her re-create a sense of family after the loss of her mother, and stepped in to help care for Nona’s seventy-something dad. With her friend Emma Bee Bernstein, Nona road-tripped across the country interviewing people about their views of feminism for the 2009 book Girldrive. She also organized her mother’s archive at the Radcliffe Institute, produced a star-studded conference at NYU called “Sex, Hope, and Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Writings of Ellen Willis,” and edited two award-winning collections of essays (Out of the Vinyl Deeps in 2011 and The Essential Ellen Willis in 2014). It was during this time that I got to know Nona a bit. I attended the NYU conference. I wrote the foreword to Girldrive and hooked her up with my family during her Midwest leg. Nona interviewed me for The Essential Ellen Willis book trailer her husband Aaron was making, and Aaron and I worked together on several short video pieces during my four-year stint at the Feminist Press. Then, pandemic, and I lost touch with both of them until this past March, when I interviewed Nona after reading an ARC of Bad Sex: Truth, Pleasure, and an Unfinished Revolution.

BAD SEX OPENS in the dark days of late 2016, with Hillary’s latest Charlie-Brown kickoff reminding the world that you’ll never go broke betting on misogyny. Trump as world leader is just one crisis for Nona, though. Her larger-than-life father, Stanley, has suffered a massive stroke, and she’s on the verge of blowing up her marriage over “bad sex.” She felt “unimaginative and codependent” compared to her mother and other world-shaking feminists, but it was almost impossible to imagine life without this loyal, affectionate partner. A committed relationship was “this thing I’d really wanted and that I’d achieved, in the era of not having to settle,” she told me when we spoke, and the fact that it wasn’t working was “embarrassing” to admit.

Nona needed some maternal advice, and so she returned to the archive at Radcliffe and studied her mother’s attempts to sort out the burning questions. “Women’s sexual feelings have been stifled and distorted not only by men and men’s ideas,” Ellen Willis wrote in 1981, echoing Nona’s despair, “but by our own desperate strategies for living in and with a sexist, sexually repressive culture.” Nona had read her mother’s articles, journals, and letters before, but in 2016, they provided wholly different insights. “I couldn’t relate to my mother going through the things she went through in her late twenties and thirties,” Nona told me, “not until I repeated her life in some ways.”

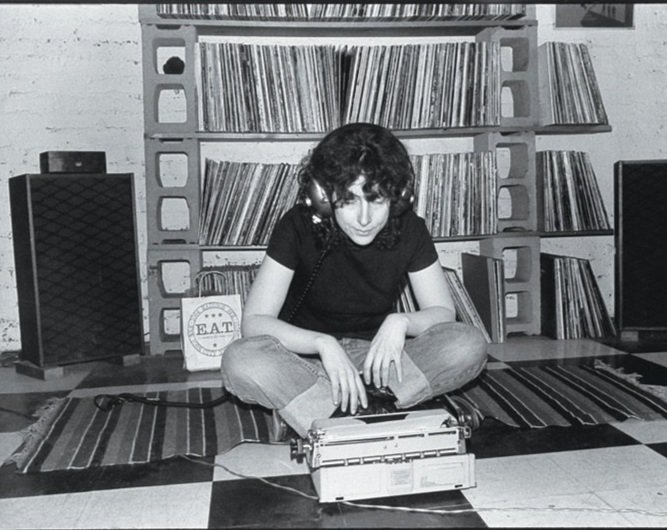

As Nona recounts in Bad Sex, her mother married at twenty, not for health insurance but because she wanted to follow her boyfriend to his fellowship, and, in the early 1960s, cohabitation outside of marriage wasn’t an option. Two years later, divorced and back in New York, Ellen worked at a magazine and lived in an East Village studio apartment with her “cocky” rock critic boyfriend, Robert Christgau. Commentary wanted a piece about Bob Dylan and Christgau suggested Ellen for it. Her seven-thousand-word piece, “The Sound of Bob Dylan,” prompted The New Yorker to hire her as their first pop music critic. After some initial hesitation, Ellen joined women’s liberation and soon helped to plan the first abortion speakout, cofounded Redstockings, and developed foundational theory such as the “pro-woman line.” This threw her “mentor-neophyte” dynamic with Christgau into feminism’s klieg light. “Consciousness raising has one terrible result,” Willis observed in her journal at the time. “It makes you more conscious.” A sweet draft resister named Steve, part of the GI coffeehouse project, enabled Ellen to wiggle out from under Christgau—Ellen had “had it with repression, had it with so many years of bottling up.”

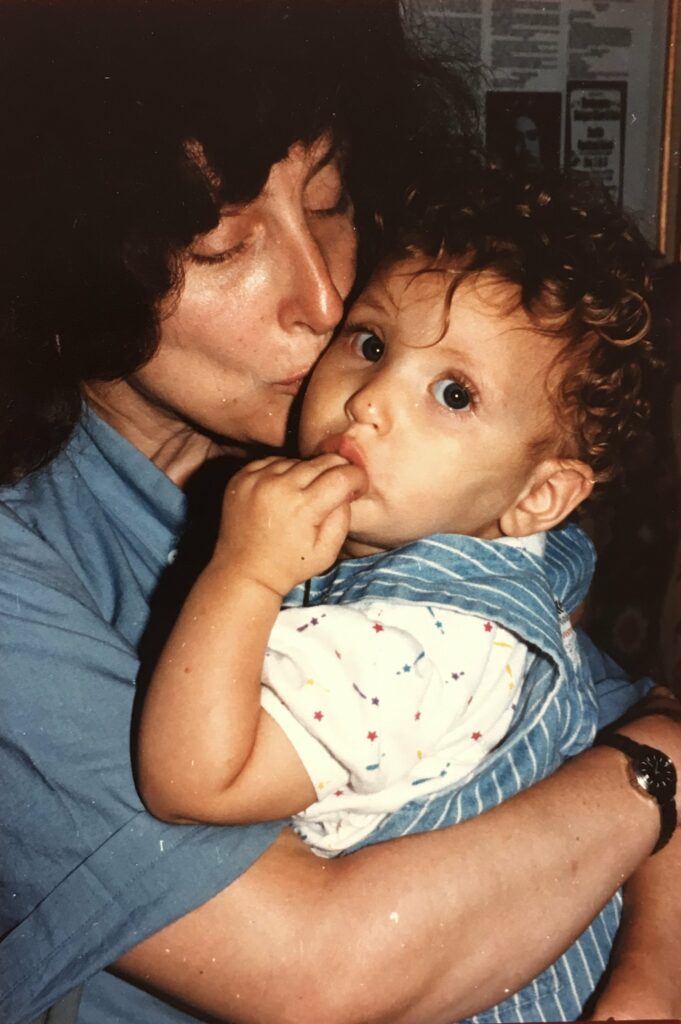

When Ellen broke up with Steve, she was single, not unhappily, for several years. Having personally helped to transform the culture, Ellen wrote in her journals that she felt “strong enough” to love a man again—even to marry—without losing herself. Enter, stage left: Stanley Aronowitz, brilliant, a “husky hedonist,” a charming womanizer, a raconteur, a great listener. “What a big fish I’ve pulled in,” Ellen remarked to her cousin. Nona came a few years later and grew up nestled in the intimacy of their twenty-five-year love, a home full of “laughs and mealtime debates.” Ellen was not “the type to dole out lifestyle edicts” to anyone, certainly not her daughter. When young Nona was obsessed with Disney princesses, her mother “didn’t flinch.” When Nona wore a push-up bra and skimpy outfits to high school, Ellen offered not a critical word or eyeroll.

“Still,” Nona told me, “I really do wish I’d gotten more of my mother’s wisdom and guidance earlier in life. She just never sat me down and talked about any of these things.” Things like Plan B, which Nona needed at age fifteen. After trying to find it herself via internet research (hard to do in 1999) and asking a friend’s mom, Ellen at last picked up on her daughter’s distress. “She just called her gyno and got me what I needed,” Nona recalls, but then . . . crickets.

I’m sure she had a whole internal dialogue about what the best move was or was she invading my privacy if she asked more questions? Honestly, my answer to that is “no.” I’m a sex and love advice columnist for Teen Vogue. I always advise people, if they have any sort of functional relationship with their parents, to try to clue them in. With my mom, it might’ve been her shyness.

I WOULDN’T CALL Nona shy. I’d call her sexy, smart, funny, curvy, curly, and not repressed—except, in her youth, when it came to admitting she wanted more from a guy than casual sex. Growing up in the 1990s, she admired what she calls “super sluts,” pop culture icons like Lil’ Kim or Samantha from Sex in the City, who performed a warped version of pro-sex feminism. “I was watching MTV and seeing Jenny McCarthy and all these cool, hang-with-the-dudes bimbos, you know?” she says. “They were not feminist, really, but also not neurotic and just up for anything. That was the vibe I wanted to emulate.” But just as the sexual revolution replaced “good girls don’t” with “only uptight girls won’t,” the Chill Girl who doesn’t need more became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In 2008, Nona shed her Chill-Girl armor to wed Aaron at City Hall. She contrasted their union with typical bougie married couples: “No rings, no checks, no ’til death do us part, just a gesture of love from an insured person to an uninsured one,” Nona liked to say. But other benefits came unbidden: once married, elders treated Nona like an adult, suburban coworkers saw her as normal, Aaron’s relatives welcomed her as family, sleazy guys took no for answer.

Despite marriage’s “alluring social acceptance,” as the bloom faded, she found that she dreaded sex with Aaron, and as the one element of their marriage that didn’t confer a social benefit, sex was the clearest indicator that something was wrong. “It’s not like he abused me or did something obvious” that rendered her a victim. “It was more about me not being honest with myself for many years. Self-honesty requires that you pull back all those layers of politics and consciousness-raising and everybody’s expectations, including feminist expectations.”

As a narrator, Nona is a generous host, holding our elbow, chatting about little-known feminist history, introducing us to the interesting writers and thinkers that populate her personal bildungsroman. The book’s perspective on her parents is especially moving—raw but not self-exploitative, as when she offers three views of a rupture in her parents’ relationship via her mother’s diaries. The first entry is dated 1981. Ellen senses Stanley’s cheating. She ponders his tricky statement “when I’m in love I’m monogamous,” trying to untangle it from the implication that she couldn’t keep this sexy “big fish” interested. Also, how to square her sincere belief that “compulsive monogamy is joyless” with her need for “spontaneous monogamy,” i.e. Stanley choosing to be with her and her alone.

By 1982, Ellen knows he’s having an affair, but since Stanley insists on denying it, she is unsure of how to start over. She’s also pregnant with Nona, clinging to hope that “joy in the baby will bring us closer (sound of cynical laughter by hordes of parents . . .).”

In grimly lucid moments I feel the awful sinking conviction that something is dead or dying—namely the terrible hope that we can have a kind of love the world tells us is impossible. At the same time I feel this incredible tenderness toward S.—tenderness and desire . . .”

Last, a fictionalized account which Ellen penned more than twenty years later, speaking what she repressed through a character named Louise:

We are not even married, and you are treating me exactly like a traditional wife. I get to be the stable boring partner who takes second place to TV and gets lied to and patronized, someone else gets to have the passion and to know more about what’s going on in my life that I do. . . . What fucking sexist shit!

Bad Sex excels in these complex moments, never losing sight of this painful rupture as one part of a long, authentically loving union, and illustrating how political sophistication can provide cover for bad practices. Feminism is powerful, Nona believes, but it can’t save us from heartbreak and loss. In a surprising (to me) digression about free-love icon Emma Goldman, we see she, too, was tormented by jealousy and obsession during her affair with Ben “Hobo King” Reitman, “a rakish radical gynecologist who treated prostitutes and other outcasts for STIs.” (Nona, who is erudite and hilarious, offers many such historical anecdotes.) Goldman’s passion for Reitman threatened her own commitment to free love, shattering her sense of mission and self, and the affair gets almost no ink in Goldman’s autobiography.

After years of applying consciousness to experience, Ellen Willis, the woman who coined the term pro-sex feminism, came to accept her “very basic” commitment to heterosexual sex as well as her need for “love and companionship.” Nona’s own preferences for blowjobs and what she calls her “agnosticism toward orgasms” have meaning, too, she writes, but they don’t mean she’s a bad feminist. While Ellen and Nona affirm feminism as a tool for liberation, they believe in the power of desire, even when it’s politically inconvenient or contradictory. .

A radical, pro-sex feminist mother is a privilege too few people enjoy. Looking ahead to her own relationship with Doris Fern, Nona wants to build on Ellen’s legacy, with a few tweaks. “Even if she’s a little embarrassed, I think I’m going to talk a little more explicitly about all of this,” Nona told me, “so she feels supported and knows there is somebody who understands, even if I’m, like, her dorky mom.”