FEMINISTS, HORROR HOUNDS, metalheads, and cinephiles descended on Chicago’s Music Box Theatre in September 2022 for a fundraiser screening of It’s Alive (1974)—an audacious horror film about a murderous mutant baby—to benefit Midwest Access Coalition. Like all abortion funds a few months after the Dobbs decision, Midwest Action Coalition was contending with a surge in patients and a crushing depletion of funds. It’s Alive is the kind of luridly entertaining, stylistically sophisticated movie the Music Box audience needed that night. The crowd response was exuberant.

The film opens on a domestic scene: Frank Davis (John P. Ryan) is awakened by his pregnant wife, Lenore (Sharon Farrell), in the middle of the night; she’s in labor. The Davis family grabs their bags and departs for the hospital. While dropping off their eleven-year-old son at a friend’s home, the couple reassure their firstborn that nothing could possibly go wrong. After waiting years to have a second child and using contraception in the interim, the Davis family is now in a state of anticipatory euphoria.

But complications arise at the hospital. Lenore is the first to know something is off (“This seems like it’s different”). Moments later, Frank sees a doctor burst through the delivery room doors and crumple to the ground, dead. Rushing in, Frank finds the corpses of medical staff on the floor and his wife screaming, “What’s wrong with my baby!” No child is in sight.

Lenore has given birth to a ferocious medical anomaly that kills whenever it’s frightened. And unfortunately, it scares easily.

With the lethal newborn on the loose and wreaking havoc across Los Angeles, police and scientists launch a baby hunt. The Davises must navigate public scrutiny and overwhelming guilt: Will they help to subdue their infant, effectively signing his death warrant, or find a way to reunite their family?

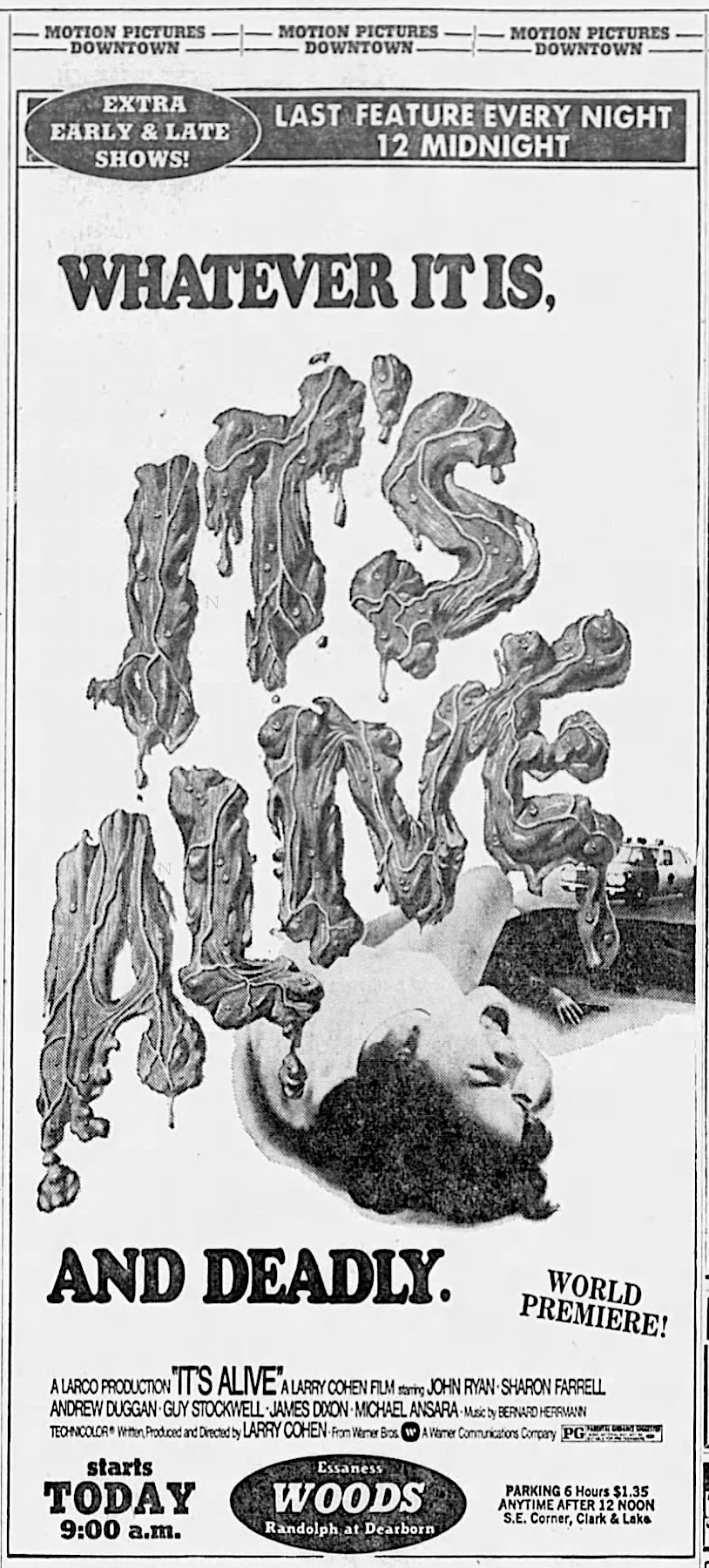

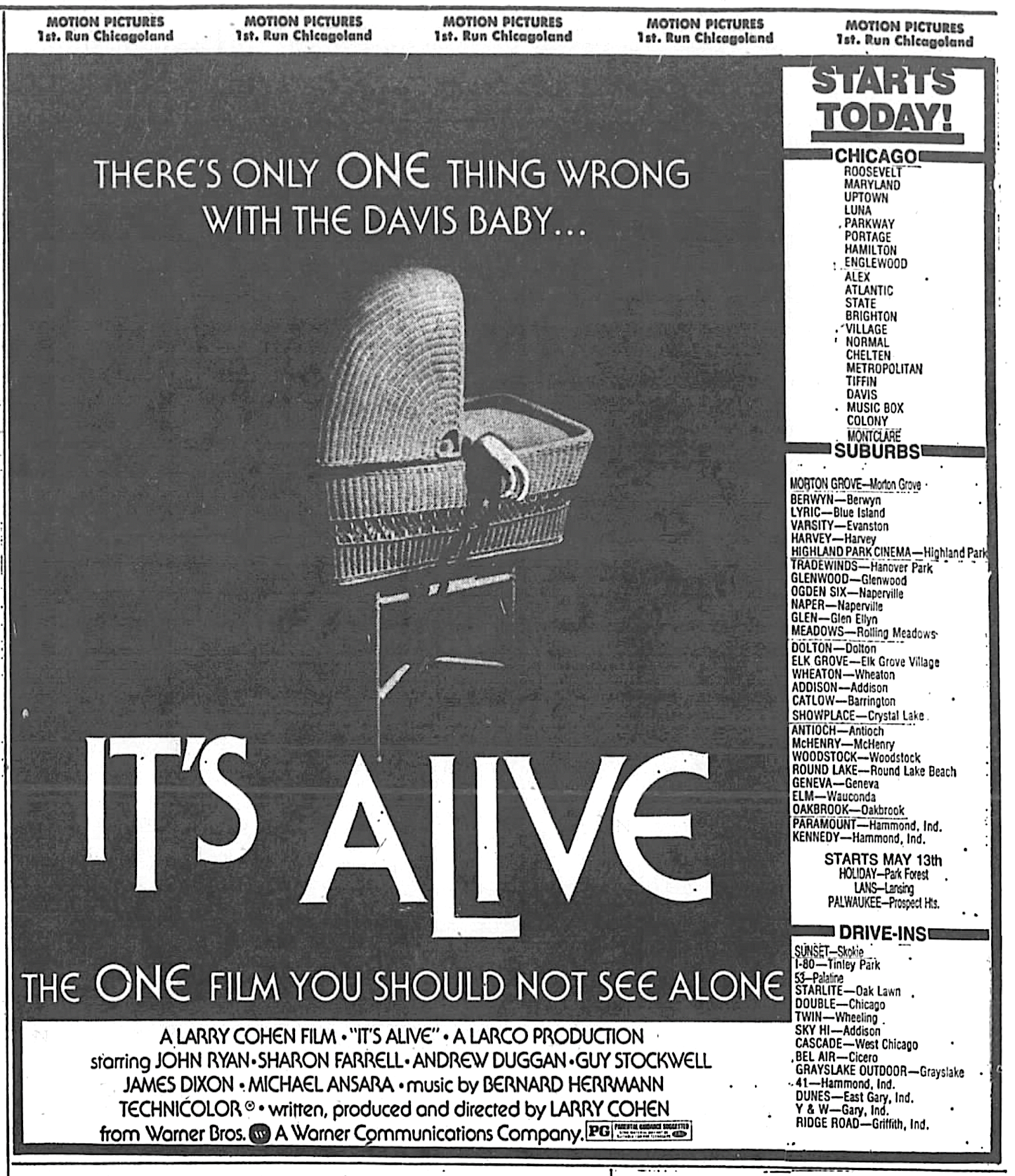

IT’S ALIVE WAS the brainchild of idiosyncratic exploitation filmmaker Larry Cohen, who began his career in the 1950s as a television writer—he created shows like the Western Branded (parodied in The Big Lebowski) and the sci-fi series The Invaders—before graduating to screenwriting. Cohen emerged as a writer-producer-director with three blaxploitation films in succession: Bone (1972), Black Caesar (1973), and Hell Up in Harlem (1973). With It’s Alive, his fourth film, Cohen solidified his trademarks as a cult filmmaker: a high-concept premise, madcap humor, sincere emotion. Cohen could squeeze production value out of a nickel and had a knack for recruiting superlative talent at the beginning or end of their careers. A young Rick Baker—who went on to do An American Werewolf in London (1981) and Michael Jackson: Thriller (1983), among others—did the monster effects, for instance; a mature Bernard Herrmann (a frequent Hitchcock collaborator) wrote the film’s eerie score.

It’s Alive is thoroughly entertaining; entire set pieces have an ironic subtext. The opening credits roll inside a womb during conception. The mutant baby attacks police in a school, surrounded by finger paintings and toy blocks. The camera lingers on a sign on the back of an ice-cream truck that reads STOP CHILDREN. A cop inspecting one of the baby’s victims deadpans, “People without children don’t realize how lucky they are.” (At the Music Box, that one brought the house down.)

It’s Alive is clearly indebted to Frankenstein, both Mary Shelley’s novel and James Whale’s 1931 film (the title alludes to Colin Clive’s iconic line as he reanimates the monster). Like Frankenstein, the film is a parable about the dangers of creation and the responsibility and uncertainty of parenthood. (It’s possible that Cohen was also influenced by Ray Bradbury’s 1946 short story The Small Assassin, another tale about a Los Angeles couple confronting their deadly newborn.) Yet the lineage of It’s Alive is rooted in a cinematic trend that first appeared during the height of the Baby Boom and Cold War, when the youth population exploded and new science and literature about child-rearing proliferated, along with crushing conformity, the ideal of the nuclear family, and the threat of nuclear disaster. With children seemingly hijacking the culture, the parental anxieties of the 1950s began to manifest in a series of thrillers where kids were the villains. One of the earliest forebears of the subgenre is The Bad Seed (1956), about a devious eight-year-old girl who hides her deadly intent beneath pigtails and sweetness. Another early entry is the British chiller Village of the Damned (1960), about a small community where all the women are simultaneously impregnated by an alien race and subsequently give birth to a breed of telepathic, albino offspring hell-bent on world domination. For the first time in pop culture, children were scary.

The critical and commercial success of Rosemary’s Baby (1968)—in which Mia Farrow’s character is roofied, raped, and forced to carry the Antichrist to term—kicked off a golden age of parental horror, spawning demonic kid films like The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), and Cathy’s Curse (1977). As with previous periods, many parental horror films of the 1970s directly reflected the phobias and events of their era. The Demon Seed (1977), starring Julie Christie as a child psychologist menaced by a computer trying to mate with her, explored the dangers of AI. Skyrocketing divorce rates and Boomer flirtations with new-age medicine showed up in The Brood (1979). The Three Mile Island nuclear disaster (1979) was mined in The Children (1980), a low-budget quickie about kids exposed to radioactive waste that vaporize any adult they touch.

FIRST RELEASED BARELY a year after the Roe decision, It’s Alive reflects the ambivalence of a culture unused to women having legal power over their bodies and reproductive lives. Early scenes reveal that the Davises considered an abortion before deciding to carry the child to term, seemingly because the first go-around was too stressful for Frank. Just before Lenore is ushered into the delivery room, she asks her husband, “It’s not going to tie you down, is it, sweetheart? You’re not going to feel trapped like you did last time?” After the birth of their child, a doctor raises a judgmental eyebrow about the abortion they initially sought. “Doesn’t everybody inquire about it nowadays? It’s just a question of convenience,” Frank snaps. “And we decided to have the baby.” (A cop in the room wryly adds, “We all make mistakes.”)

Though the cause of the baby’s mutation is never definitively revealed—lead poisoning, smog, chemical pollution, and radiation are all theorized—Lenore’s birth control pills may be the culprit. A modern viewer might interpret this plot point as a sexist commentary on sexual freedom and contraception. By the early 1970s, however, the Our Bodies Ourselves-style women’s health movement was in full flower, bringing informed consent and patients’ rights to the feminist movement. Barbara Seaman’s The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill (1969) had prompted Senate hearings about the deadly dangers of the high-dose birth control pill and mandated that potential side effects be listed on the package of every drug. The culture was reckoning with decades of blanket-prescribing pills to pregnant women with tragic outcomes. For instance, diethylstilbestrol (DES), given to millions of women from 1940 to 1971 to stave off miscarriage, resulted in a surge of rare vaginal cancers in their daughters. Likewise, the Nazi-formulated tranquilizer thalidomide, available without a prescription to combat morning sickness until the early 1960s, resulted in more than ten thousand babies with severe, often-fatal birth defects. It’s Alive takes the ruthless menace of Big Pharma further: the same company that peddled toxic contraception to Lenore now plots to cover its tracks by capturing the Davis baby.

It’s Alive reflects the ambivalence of a culture unused to women having legal power over their bodies.

The drug company is the villain here, but who is the victim? As the Davis patriarch, John P. Ryan gives a stunning method performance—giddy, expectant dad transformed into a disgraced father denying his offspring, frequently repeating the line, “It’s no relation to me!” When Frank confronts his grotesque offspring in the closing scenes, the performance is so moving, I forgot I was watching a monster movie.

Still, it is curious that a film about birth is so focused on the father’s emotional state and point of view while Sharon Ferrell’s Lenore spends most of the movie sidelined in a hellish postpartum daze. While cops, doctors, scientists, and her husband give speeches and decide her child’s fate, Lenore is watching Looney Tunes. In the surreal final showdown, Lenore lobbies forcefully for her child’s life. But given all we’ve seen before and since, do we really believe she is in control of anything?

To me, the way It’s Alive mixes politics, primal fear, and pure escapism is evergreen. And forty-eight years after its debut, the Music Box audience agreed, whooping and cheering as the credits rolled. With the attack on reproductive rights and other modern crises on the horizon, will the parental horror movie make a comeback? There’s certainly enough material to work with.