The other day, I received a press release sent by a publisher. He was hoping to interest me in a forthcoming memoir. It was the story of a man, driving across the country, in search of information about his father’s life. Something along these lines. A man and his father. Two men and their whatever. I thought, Jesus (as it were), another book about men excitedly wanting to know about being men—about being sons or being fathers or some such topic.

I thought of Jesus, himself, and Abraham and God, and I thought, for fuck’s sake, enough with these men and their sons and their fathers dominating our thoughts and lathering themselves up, as if their experience is important or dramatic or interesting, just because they insist it is.

The book described in the press release might be a wonderful piece of writing, sentence by sentence. It might be a thrilling literary narrative. I don’t know, and I will never know, because I am all topped up with stories written by men about being men that are excitedly addressed to other men. Like in all bibles and most literature that has ever been written in any language.

If women are imagined reading narratives written by men about what it means to be a man and that are excitedly addressed to male readers, then women readers are basically in the same position as the women in the hotel rooms of Louis C.K., asked to watch him masturbate. “Can I masturbate in front of you?” ask most books written by men about the excitement of being men, including the story of Jesus and his father and the story of Abraham and his father, and, you know, all the rest.

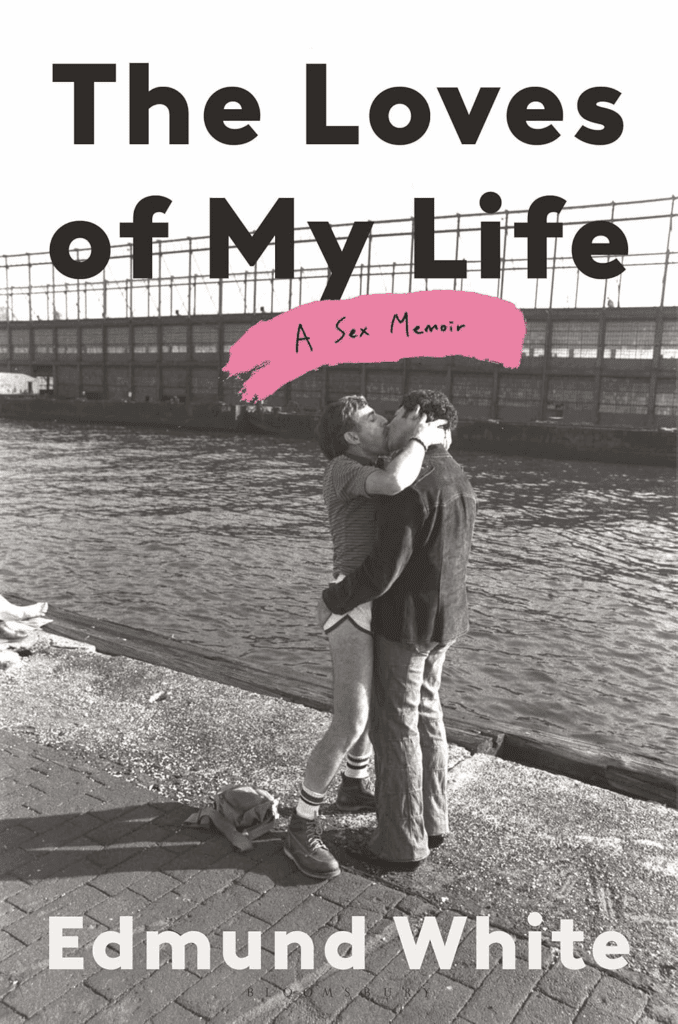

A few months ago, I was asked to review a book for a national newspaper. I said sure. It was Edmund White’s memoir of a lifetime of gay sex. I started reading it and liked it very much. White is a great and detailed stylist. He can spot a dramatic moment in a memory from a mile away and not only pounce on it but show you, with a skillful layering of memories within memories, the social and political backdrop of a scene’s time and place.

About a third of the way through, I came to a chapter crafted with language about women’s bodies and women’s lives so stunningly arresting it had to be the focus of what I’d write. The language had received a pass from the book’s editor and publisher and for all I know from the editor who assigned the book, although I doubt it because most editors don’t have time to read the books they assign.

In this case, what I mean by the pass is that no one seems to have pointed out to White what a female reader would experience reading his words. I don’t think his words should have been deleted or edited. I think an editor might have raised the issue with White of what he was expressing, how it contributes to larger harms done to women, and that maybe White’s narrator would contemplate some of this, to at least register for the reader that the writer observes what he is saying.

If White’s erotic fantasy life involved imagining himself debased in the body of a person of color, let’s say, or a person understood to be poor and underclass, White’s editor would have spoken up. Of this I have no doubt. No one wants their author to be seen as a racist or a social imperialist. Describing the female body as a putrid biological condition, well okay then, no harm done to White’s reputation there.

This is the review I wrote:

Pretend you are a woman. Pretend you are me. It’s a thought experiment. It won’t take long, and I promise you can return to being whatever you are, or think you are, or want to be. Pretend you are me, and you are reading The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir, by the renowned prose stylist Edmund White, who actually is a great prose stylist, there’s no argument with that, or else how could I have read an entire book that is basically a list of fondly recalled fucks he had with men.

About a third of the way through, you come to a chapter called “Pedro” and you read these passages:

We decided it was exciting to call my ass my “pussy.” There’s something so low, so dirty and humiliating, about that word if applied to a man, something so smelly and endocrinal, so soppy with animal secretions, that it repulses and shames at the same time. I have no idea whether coño has the same impact in Spanish, but after a few drinks Pedro liked pussy and cunt talk. It felt a bit less abjectly menstrual in another language. . . .

Sometimes he’d seem disgusted with . . . my insatiable need for cock. . . . His certainty that I was voracious reminded me of the nineteenth-century male fantasy of the devouring woman who destroyed man. She was a lioness licking her paws, presenting her inflamed cunt to the poor, bewildered males, despoiling them of their family and fortune by revealing a glimpse of the hairy clam under whitecaps of the lace. Her bed an altar to demeaning, insatiable lust . . . capable of witnessing a young man destroy his ambitions, fortune, and health, the length of his shaft sunk into the greedy, putrescent origin of the world, bubbling sulphurously amid the overgrown underbrush.

So, you’re me, a female human with the body parts referred to in White’s text, and although it isn’t lost on you the author is showing off the playful leaps of his imagination, it’s not lost on you because you have spent your life seeing your body and the life lived in that body misidentified by male writers to such an exaggerated degree it’s comical if you are in a certain mood. You have spent your life in this situation, and you can feel loathing and admiration at the same time.

What you loathe is not the comparison of an asshole to a cunt. They are two orifices you can penetrate sexually. What angers you is the way the male person happily slums in your sexuality, knowing that whatever disgust he may feel about his own body and sexual acts, he can console himself that at least he doesn’t actually go through life in the smelly, menstrual body

of a woman.

If you are not in the mood to find White’s words comical, you take it for granted that men, gay and straight, do not tax themselves imaginatively to wonder how their words about women will land on actual women. You are so familiar with this experience, you continue reading, because what are you going to do, throw nearly every piece of writing by a man across the room and watch the bindings of their books break into dust and their pages scatter?

Sure, go ahead. You are free to. I pleasurably read on, finding much to enjoy in White’s often brilliantly detailed scenes of sex before AIDS, before even herpes. White, who is eighty-five, began having sex in his early teens and kept going for decades with boyfriends, tricks, and paid partners until relatively recently, when he tells us he became impotent. Here, he’s conjuring an apartment shared by men he was close to “at the foot of Christopher Street overflowing with greasy wrappers from ordered-in fast food, jockstraps dangling from the shower curtain rod, pink plastic bongs over a reservoir of water, the smell of poppers and vomit, a room full of a couch in many sections, a shag rug with cigarette holes burned into it, an empty fridge with just a frosty jar of pickles and a Coke can laboring under Pleistocene layers of ice. A toaster oven that no longer worked; a roasted fly was sitting on top of it like a symbol.”

This apartment is every apartment in a certain time and place that doesn’t exist in reality but in the memories you write now. As White flips through the index cards of his adventures, you can go with him, back to when sex was separate in our minds from dying of a disease. You thought about sex with people you knew, people you loved, people you would never speak to—a man I can still see standing in the door of a subway car. I wanted to know what people were talking about when they talked about sex. So did Edmund White.

I knew the piece I wrote would be rejected. I sent it in anyway, because I thought what I had written was important. The editor said he couldn’t publish the piece as I’d written it. He said he couldn’t publish the passages from White’s book I quoted in order to make my points because they would offend the paper’s readers. So, are you digging this? The paper can’t quote writing from a book it assigned that would throw light on the pass because throwing light on the pass is the offense.