Like Eiren Caffall, I have spent many hours in the Long Island Sound. On its beaches I have watched tiny barnacles feed in the tide, ospreys hunt for fish, horseshoe crabs scuttle like living fossils in the surf. And then there were the jellyfish. They appeared one day out of nowhere. A bloom that filled the entire harbor, translucent bells bobbing just under the surface of the water, then disappearing again into its murky depths. I was in my thirties, living in a town on the edge of the Sound with my husband and our three children. The sight was awesome, in the original sense of the word. As I watched the jellyfish that day, there were things I knew and things I didn’t. I knew that the bloom’s beauty foretold something terrible—the warming earth, the collapse of marine ecosystems.

Caffall’s memoir threads two topics—how the ocean is dying, how genetic disease can devastate a family—into a shimmering tapestry of grief and wonder. Caffall grew up visiting the Long Island Sound with a father who grew sicker each year from polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a life-threatening genetic disorder. Caffall’s family calls it the Caffall Curse. The disease has struck every generation of Caffall’s paternal family for 150 years. As an adult, Caffall learned that she too inherited it.

“I know how to end PKD in one generation,” a nephrologist tells her. “People like you should never have children.”

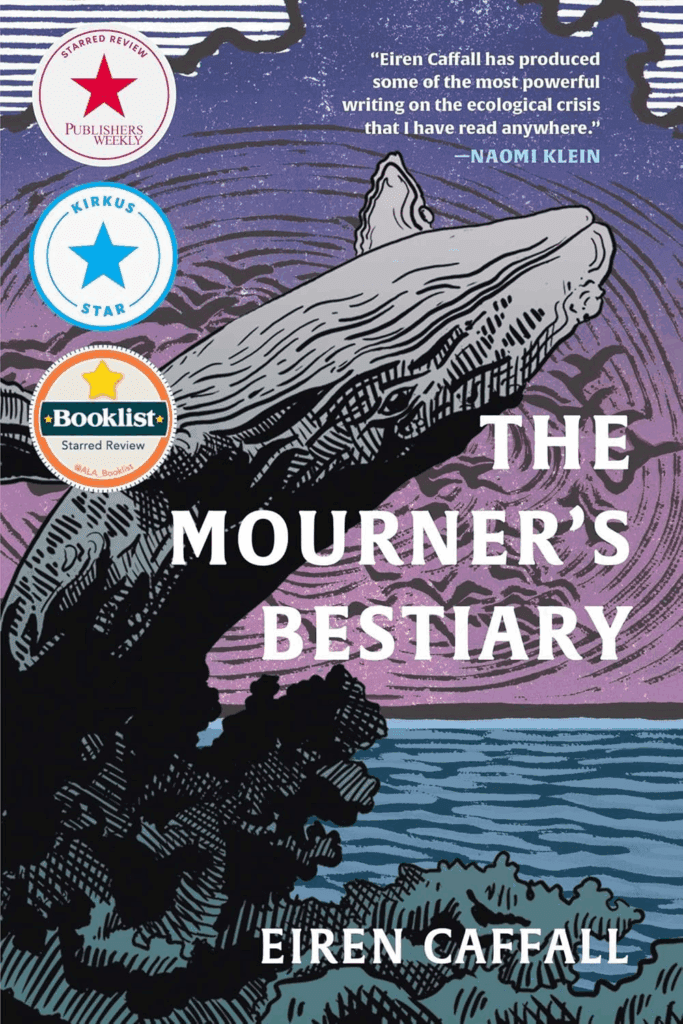

We know from the first page that Caffall will reject this doctor’s prescription and have a child, Dex, “the last of our line.” The book opens as Caffall and Dex take a trip to coastal Maine and meet a boy who has caught a squid in a bucket. Iridescent and red-eyed, “a slender bag of hydrostatic wonder,” the squid is our introduction to the bestiary. Caffall is quick to the metaphor: “I was raised by the expendable ill, alongside threatened sea creatures in collapsing oceans—tender beings caught in extinction. My whole family was like them, brave and chaotic, poisoned by things outside their control.” Caffall and Dex are staying on a small island when Caffall falls and has a seizure; a storm is coming, so the Coast Guard ferries the two of them to the mainland hospital. Caffall faces her own loss of control. As a single mother, away from everyone they know, she will have to figure out how to care for Dex and get them home.

The trip with the seizure is the current that carries us through the book, but Caffall charts a course for us into the past too, eddies of memory where we will enter her childhood and meet her family’s dead. Here we see how the Caffall Curse takes hold, its effects reaching far beyond the body.

PKD causes cysts to bloom—like the jellyfish in the harbor—inside the kidneys, taking over, destroying their normal function. The metaphor is mine, but Caffall might appreciate it. She constructs her bestiary so that each chapter is named for a different marine animal that she encounters in the Sound or along the coast of Maine. She tells us that animal’s story—how it lives, how human disruption of the environment has affected it—and then connects it to the illness and grief in her family’s story. Sometimes the device works well, sometimes less so.

In “Dinoflagellate Microalgae,” Caffall recounts her PKD diagnosis at age twenty-two, a doctor who offers a grim prognosis. “My family drowned under the news,” she writes. She frames this chapter around bioluminescent algae, remembering a magical encounter with them when she was younger: “I’d never been naked in the ocean, in the dark, and the water was warmer than the air, salty and buoyant. Around us the water lit up.” After her diagnosis, looking for answers, she seeks out nature and finds that “every spark is a clue, every shimmer in the black ocean a way to something more luminous and complex. . . . The universe was so much bigger than the fears that I was carrying.”

In “Common Periwinkle,” she weaves ecological descriptions of an invasive snail with the history of her uncle, Brian, whose fear of an early PKD death keeps him from planning for the future. By the time he learns he is the only Caffall of his generation to escape PKD, the Curse has taken its toll anyway. He begins showing concerning symptoms of another disease, but he is poor, with no health insurance; his diagnosis of AIDS comes too late for the treatments available to save him. Caffall meditates here on how to live when we are facing destruction. The invasive periwinkle wreaks havoc on Maine’s coastal ecosystem, but another visitor to the island teaches Caffall to pick up the snails and sing to them. In response to the sound, “their eyestalks emerge into the sunlight,” a moment Caffall describes as a miracle. “I understand the urge to look only at the end we face,” she writes, drawing the link between ecological disaster and illness, “and not at the amazement.”

The chapter where Caffall’s mother dies of cancer is particularly moving. In hospice, her mother suffers from terminal agitation, which makes her say cruel things. Caffall’s past anger at her mother—over the collapse of her parents’ marriage, her mother’s alcoholism—comes rushing back. She braids this chapter with the North American right whale, an animal that has suffered catastrophic population declines. A right whale expert, who has spent decades watching these mammals die, tells her, “I’ve stopped using the phrase, Something bad happened to me. I’ve begun to use the phrase, Something powerful happened to me.” Bearing witness to loss, “holding the mystery,” Caffall comes to understand, can be transformative.

Perhaps more than any other book I have read recently, The Mourner’s Bestiary has a structure that echoes its subject. Caffall writes in long, swirling sentences that flow like water. The narrative moves from family to ecology and back like the crest and trough of waves. The reader is not propelled through the narrative but gently rocked by its tides. Her writing is often beautiful, poetic. These same qualities that set the book apart are also its flaws. At times, her long sentences try to contain the whole world and lose focus, blunting the impact of her words. Sometimes the narrative structure becomes hard to follow. But as I kept reading, I learned to let the words carry me. We are not in control, the book reminds us; we must go where the water takes us.

A few years after I saw the jellyfish bloom, my husband was diagnosed with familial cardiomyopathy. Painful electrical storms left his heart failing, completely dependent on a pacemaker by forty-one. Like PKD, his disease is passed down through a dominant gene, meaning the child of an affected parent has a 50 percent chance of developing the disease too. But while Caffall was diagnosed before she decided to have children, my husband was diagnosed after. One of our kids had already inherited the gene. As I see my husband’s suffering, it is impossible not to fear that this is what our son’s future contains too.

If we had known earlier, would we still have decided to have children? It’s easy to say that people with genetic disorders should not have children. I know how to end PKD in one generation. Caffall wrestles with her choice, haunted by the doctor’s words. When her father is dying of complications of PKD, she expresses doubt about ever having children to an old family friend. “You wouldn’t want [your dad] not to be here? Would you?” the friend replies. As Caffall sprinkles her father’s ashes in a river, she decides the friend is right. “All I wanted was another second with him, and it didn’t matter that the second I’d get back was one where he and I both had PDK. . . . I was worthy of being alive, and my father was too, and any child I had would be as well.”

Reading The Mourner’s Bestiary,I remembered a time in college when a friend and I went to the zoo. All around us were animals threatened with extinction. “Extinction is a natural process,” the friend mused. “Why does it matter if we save animals if they’re going to go extinct eventually anyway?” Caffall’s book reminds us why we should save them. She shows us how right whale mothers make soothing noises to their calves when a shark passes by, how a caught lobster tries to wriggle back to the sea, how marine animals are changing ancient feeding patterns in response to a warming ocean. Animals, like us, want to live. It is worth saving wildlife even if it will go extinct. It is worth helping the sick even if they will die. In mourning—for her family, for the environment—Caffall makes the case for life itself. She reminds us it is not the end that matters. It is the amazement.