Like all first signs, it was easy to dismiss. Even more so since it came from an English teenage model. I was hanging out with her godmother during Paris fashion week about five years ago. As we left an event and passed a scrum on the streets, the girl stopped in her tracks. She’d seen a member of BTS. I was barely aware of what that was. A Korean boy band?

The second sign, three years ago, puzzled and amused me. A British man in his mid-fifties told me he’d obsessively watched Korean cooking lessons by a female chef during lockdown. “It wasn’t sexual,” he assured me as I stared. A kimchi enthusiast, he announced that now he could make his own, to the chagrin of his girlfriend, who objected to the mess and smells. I raised my eyebrows ever so discreetly. Kimchi is notoriously difficult to get right. It can take a lifetime if you’re lucky. I chalked up his passion to being an English eccentric as I’d once seen him wearing a red poncho, a souvenir from a South American trip. I wondered where he found the ingredients; London, unlike New York or Los Angeles, had no Korean groceries in 2020.

This past year, I had lunch with an English aristocrat who not only watched Korean dramas but traveled to London from her country house to take Korean language lessons—the “highlight” of her week, she said! She served me kimchi made by her Korean teacher, had christened her puppy with a Korean name, and was excitedly planning her second trip to Korea. At that, the other signs rushed into my consciousness: Hallyu!, a major show on Korean pop culture at the Victoria & Albert Museum; the large Korean food shop that opened recently on Charing Cross Road in Central London; the art world flocking to Seoul for the second Seoul Frieze art fair. On my summer holiday in Kenya, a new acquaintance (from South Africa) immediately asked if I’d read The Vegetarian, the novel by Han Kang that won its author and translator the 2016 Man Booker prize.

Korean skin products rule the beauty sector and, according to the New York Times, “forward-thinking Korean contenders now dominate the city’s high-end restaurant scene the way French cuisine used to.” Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite swept the Oscars and won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2019; Squid Game, Minari, and Beef are more recent products of an economic and creative juggernaut. No country has gone from OECD1 recipient to donor faster than Korea. Just this summer, a Japanese friend told me in shocked awe that the Korean economy was poised to surpass Japan’s. For me—a 1.5 generation Korean American (I was born in Korea but arrived in the US when I was a baby) who grew up on totally white Long Island in the 1970s and 1980s—this Korea-mania is completely baffling. When I was a kid, people made snide remarks about my family for not wearing shoes at home. No one ever asked us if we were Korean; it was always “Chinese?” or “Japanese?” When I said I was Korean, people assumed I was a “war orphan” now lucky enough to live in the United States with a nice, white family. Which war? my mother wondered, aghast, since she was four at the end of the Korean War.

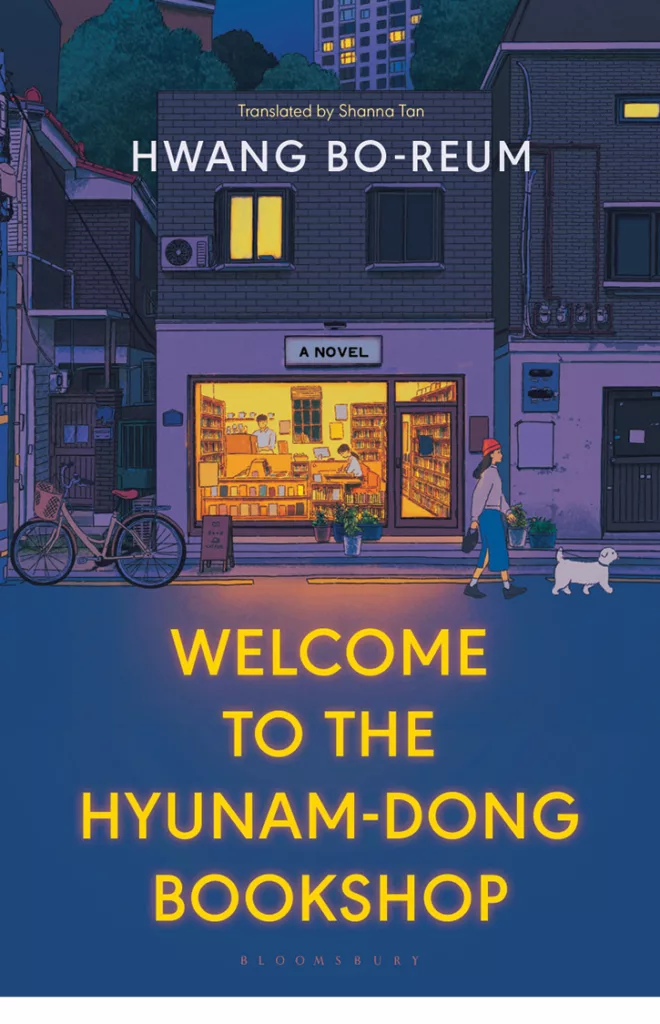

Korea-mania is the only way I can explain why Bloomsbury has published the English translation of Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop by first-time author Hwang Bo-reum (translated by Shanna Tan). Like most Korean books today, this book originated as the winner of a writing prize, which was then released as an e-book and ultimately, according to its publisher, boasted combined e-book and print sales of 150,000 copies. It’s a classic feel-good story about a middle-aged woman, Yeongju, who leaves her (unidentified) high-pressure conventional job, divorces her conventional husband (to the horror of her conventional parents), takes her half of the money from the sale of their apartment, and realizes her childhood dream: opening a bookshop in Hyunam-dong. She chooses “Hyunam-dong” because the root of “hyu” stands for “rest.”

The bookstore is her new life and represents a search for some kind of feeling, some kind of self-improvement, some kind of knowledge, some kind of escape and respite. Books seem to be Yeongju’s only passion and, fortunately, they help her: “I’ve become a better person at the bookshop. I tried to put into practice things I’ve learnt through books, and not merely leave them as stories within pages,” she tells us. “Good things in books shouldn’t just stay in ink and on paper.” Yeongju hires Minju as the café barista. Also a society dropout tired of struggling to be a high achiever, Minju keeps his phone switched off so he doesn’t have to talk to his (understandably) concerned mother. “Is my whole life a mistake?” he wonders.

The bookstore is her new life and a search for some kind of feeling, some kind of self-improvement, some kind of knowledge . . .

To her credit, Yeongju is principled and enterprising in realizing her dream. She posts little meditations about her favorite books on social media: “Every one of us is like an island; alone and lonely. It’s not a bad thing. Solitude sets us free, just as loneliness brings depth to our lives. In the novels I like, the characters are like isolated islands.” She invites authors to speak and creates book clubs, eschewing bestsellers for indie titles. She organizes a writing seminar and eventually undertakes a newspaper column. The book’s main theme is exiting the intense Korean rat race to “find oneself,” a universal desire in today’s advanced countries—a population’s need to self-actualize is evidence of having achieved first world status. Thus, the bookshop collects an assortment of predictable characters—women in unhappy marriages, a lost teen, enthusiastic bookworms, visiting authors—thereby creating a community wherein everyone can learn from the books and from each other. A bit of tame romance is sprinkled in for good measure amid other small acts of rebellion. Yeongju and her cohorts inch forward in life, trying to make sense of it, and, unsurprisingly, everyone seems to be better off by the end of the story.

Korea is an extremely conformist country pulled taut between ancient traditional values and the lure of the twenty-first-century West, so the slightest aberration—divorce, rejecting higher education, voluntarily leaving a job—has great significance. One moment in the book interested me for a reason that no one but Koreans (or perhaps other Asians) would appreciate. At a meeting of “The Book Club of Mums,” one member proposes that they call each other by their first names. This suggestion might pass by unnoticed to English readers, but Koreans of Gen X and younger would consider it risqué or an attempt to be Western. (Older generations wouldn’t even conceive of such a suggestion.) Things may have relaxed a bit, but Korea is still hierarchical and names are sacred. You do not call people by their first names, certainly not strangers, and never in business settings—only your absolute peers (classmates, for instance) and the lower ranks in familiar settings. For example, my mother was the oldest of three children, but she had no family in the United States, so the first and only time I heard anyone call her by her first name was when we visited her father in Korea when I was twelve. Otherwise, she was always addressed as “the mother of,” “older sister,” or by some kind of title, like one given to her at church. I couldn’t tell you what my grandfather’s first name is. It never came up!

My father, on the other hand, is the fourth child. Since his family lived in the United States, I heard his mother and older siblings call him by his first name constantly. But to call someone higher up by their first name is totally offensive. When my four-year-old cousin in Korea was furious at me on that trip when I was twelve, she shouted my name at me over and over. I had to ask my mother why she was doing that, and she explained that it was the worst insult. Having grown up in the United States, though, I couldn’t care less.

For the past two decades, the Korean government has doubled down on projecting soft power. Since then, many Korean books have reached international audiences due to the work of the Korean Literature Translation Institute (KLTI), a government agency. Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookstore has achieved the KLTI’s goal of globalizing Korean literature, but in this case, I am not sure of the result.

Although it was a bestseller in Korea and is likable enough, Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookstore is formulaic and clichéd—full of references to the perfect coffee, meditation, generic self-help philosophy (“A day well spent is a life well lived”), and admiration for The Catcher in the Rye. Except for a few Korean words here and there (which I think could use some explanation and be better transliterated), the novel could take place in Seattle. (Maybe this is why Bloomsbury is publishing it? It’s utterly familiar.) To be fair, many great and captivating stories, including classics, concern themselves with the mundane—Jane Austen’s Emma, James Joyce’s The Dead, Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity—but whether it’s due to the translation or to the novel itself, I found it as bland as jhouk, the flavorless rice porridge Koreans eat when they’re sick.

More exciting to me is the opposite end of the spectrum. Koreans, as conformist as they are, also have a crazy, chaotic, uncontrollable side. They are the Italians of Asia. This can explain the more original and spectacular examples of Korean art—the weirdness, perversity, craziness, and violence of creations like The Vegetarian, The Handmaiden, Squid Game, and Parasite. These works manifest a mysterious kimchi-esque shock that moves the culture forward, which I prefer to the comfortable jhouk of Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookstore.

1. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development